Unconventional Wisdom: Paradigm-changing new programs at TC

Teaching for the New Majority

Unique prep for today’s diverse classrooms

“In losing black teachers, black children lost advocates and champions who set high academic standards and cared deeply about students’ success,” Amy Stuart Wells, Professor of Sociology & Education, told educators at “Reimagining Education: Teaching and Learning in Racially Diverse Schools,” a unique four-day professional training held at TC in mid-July.

“Reimagining Education” explored the history of racial and ethnic diversity in public schools and diversity’s educational benefits for today’s increasingly diverse student population.

In an opening presentation, Wells and doctoral students Lauren Fox, Diana Cordova-Cobo and Juontel White said public schools have largely re-segregated due to legal challenges, even as immigration has created a majority nonwhite student population. Whites still constitute 80 percent of the teaching force.

“By the 1970s, we started to see challenges to the common wisdom about children of color as ‘culturally deprived,’” said keynote speaker Sonia Nieto, Professor Emerita of Language, Literacy & Culture at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. The task now: to develop culturally responsive pedagogy that addresses “attitudes, behaviors and dispositions” and the institutional racism that sustains them.

“Reimagining Education” featured student rap artists who teach science and social studies through their music and a ballet performance by students from immigrant families. Workshops included:

“Reading, Writing, and Talk: Inclusive Teaching Strategies for Diverse Learners.” Mariana Souto-Manning, TC Associate Professor of Early Childhood Education, immersed participants in difficulties experienced by children whose “home language is not aligned” with their school’s.

“Developing Racial Literacy with Children’s Literature.” Led by Detra Price-Dennis, TC Assistant Professor of Elementary & Inclusive Education, teachers learned about Jim Crow-era “green books” that guided black travelers.

“Using Hip Hop as Therapy in Multi-Racial Schools.” Counseling Psychology Ph.D. student Ian Levy demonstrated the hip-hop and rap workshops he uses with Bronx high school students.

TC Associate Professor of Science Education Christopher Emdin argued that standardized tests can prevent meaningful connection with minority students. “Rigor,” he declared, “is not equal to rigor mortis.” — Patricia Lamiell

Schoolhouse Lawyers

“We’re putting in civil rights guardrails, but the states will make decisions about interventions and using federal funds.”

—John King (Ed.D.'08), U.S. Secretary of Education

King (Ed.D. ’08), a former high school social studies teacher, did just that for students in TC’s annual School Law Institute in July. The Secretary headlined the week’s rock-star instructor lineup, which included Gary Orfield and Patricia Gándara, co-directors of the UCLA Civil Rights Project and leading authorities on school desegregation, affirmative action and serving immigrant students; TC Professor Michael Rebell, a prominent national authority on school-finance law and the right to an adequate education; and Dennis Parker, Director of the ACLU National Office’s Racial Justice Program. The Institute’s Faculty Chair, TC Professor of Law & Education Jay Heubert, litigated race-discrimination cases as a civil-rights lawyer at the Department of Justice and served as chief counsel to the Pennsylvania Department of Education. Institute Co-Chair Rhoda Schneider is General Counsel and Senior Associate Commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education and has repeatedly served as the state’s interim Education Commissioner.

Like No Child Left Behind before it, ESSA commits states to college and career standards and continued close attention to achievement gaps. Yet it also requires use of non-academic indicators such as student engagement or school climate, while scaling back federal control. “We’re putting in civil rights guardrails,” King said, “but states will make decisions about interventions and using federal funds.”

“Leaving it up to the states creates some problems,” King acknowledged. Does inclusive debate simply beget “fluffy indicators that let schools off the hook”? How will besieged state education departments manage the new measures?

Still, it was clear that considerations like school climate matter to King. He closed by recalling losing both his parents as a young boy and later being asked to leave boarding school. He wished the school had offered more options for students in difficulty.

Later, English Education Ph.D. student Valon Beasley emailed: “Secretary King made me know that he is listening and he is watching the tragedies and inequities that African-American male youth are suffering from today. I will use his life and words to motivate and transform the minds of New York students, various educators and hopefully, diverse people in the world.” — Joe Levine

The 2017 School Law Institute runs July 10-14. For information visit www.tc.edu/schoollaw.

The Art of Teaching Nursing Teachers

“Nurse educators have one of the hardest jobs in higher education. Often, aspiring nurses have no college degree, are young, naive and very inexperienced.”

—Kathleen O’Connell, Isabel Maitland Stewart Professor of Nursing Education

“There are not many programs aimed at teaching teachers how to teach,” she says.

Enter Teachers College’s new nursing education doctoral program, launched this fall with Nwabueze in its inaugural cohort. The new program is offered fully online to students with a master’s degree in nursing who want to become leaders in the academic or health care setting without missing a beat on the job.

“TC’s program is truly unique in that students engage in scholarly discussions, interactive classes and collaborative research projects through an online environment,” says lecturer Tresa Dusaj.

More than 60 percent of registered nurses-in-training lack a bachelor’s degree.

“Nurse educators have one of the hardest jobs in higher education,” says Professor Kathleen O’Connell, the program’s creator and founding director. “Often, aspiring nurses have no college degree, are young, naive and very inexperienced. The job of the nurse educator is to turn them into safe and responsible professionals in a very short time.”

TC launched the nation’s first university-based nursing education program in 1898 and produced thousands of leading nurse educators. Nursing schools subsequently took over preparation of nurse educators — but with 1,200-plus nursing faculty vacancies nationwide due to a lack of candidates with doctoral degrees, there’s growing sentiment that education schools should resume “teaching the teachers.” With that goal in mind, the Jonas Center for Nursing and Veterans Healthcare awarded scholarships to four students in TC’s new program — the first time the Center is funding education school students.

“I believe this program will affect how nurses are taught,” O’Connell adds. “I hope students take what they learn here, continue to further the profession’s research and become leaders in their schools and in their fields.”

— Amanda Lang

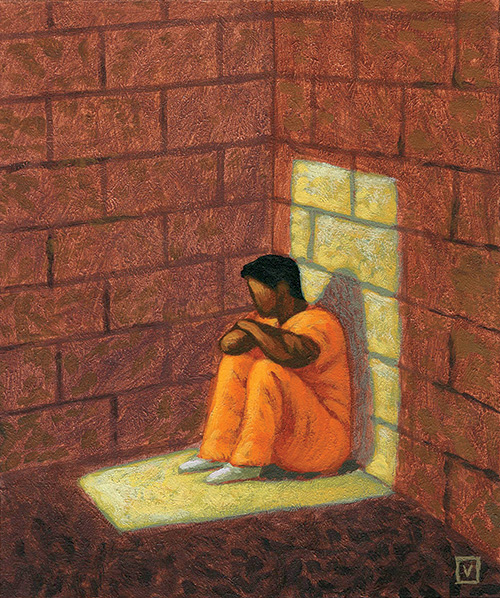

The Crime of Punishment

“You can’t be well if you spend your life in a social group that’s pressed up against the window, looking in,”

—Laura Smith, Associate Professor of Psychology & Education

Edwina Richardson-Mendelson, a longtime Administrative Judge for the New York City Family Court, was speaking at “Youth and Wellbeing in an Age of Mass Incarceration,” an August forum held by TC’s Civic Participation Project (CPP).

Created by TC’s Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz, Laura Smith and Lalitha Vasudevan, CPP provides “safe and brave spaces to discuss issues related to social justice and equity for young people in schools.” It seeks to “disrupt the academy by opening up a space for people to be who they are and want to be,” said Sealey-Ruiz, Associate Professor of English Education.

The U.S. incarceration rate is the world’s highest. African-American youth are nearly five times more likely to be confined than whites, while Latino and American Indian youth are two to three times more likely.

“Youth incarceration has infused the practices of teaching, mental health and other fields,” said Vasudevan, Associate Professor of Technology & Education.

“You can’t be well if you spend your life in a social group that’s pressed up against the window, looking in,” said Smith, Associate Professor of Psychology & Education.

“We’ve got to help teachers notice what kids are feeling,” said Suzanne Carothers of NYU’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education and Human Development. “If a five-year-old says, ‘I’m hungry,’ and you say, ‘Do your math,’ you’ve lost something.” — JOE LEVINE

First Editions

TC’s Faculty in Print

Nashville Color Line

The reality behind a desegregation success story

During the court-ordered desegregation era, Nashville, Tennessee created “one of the most statistically desegregated school systems in the country,” writes Ansley T. Erickson.

Yet in Making the Unequal Metropolis: School Desegregation and Its Limits (University of Chicago Press 2016), Erickson, Assistant Professor of History & Education, describes a school district in which “inequality had shifted form.”

“Nashville’s educational outcomes generally followed national patterns — they both improved, and remained starkly unequal,” Erickson writes. The city achieved “relative statistical success while remaining unable or unwilling to value all of the district’s students, their communities, and their places in the metropolis.” Why? Because Nashville’s housing policies, economic development agendas and urban renewal projects affected the “hundreds of small choices made by local, state, and federal officials” in enacting desegregation on the ground.

With segregation receiving renewed attention, Erickson believes today’s policy makers must understand stories like Nashville’s in order to make a genuine dent in the problem and the related issue of educational inequality.

“Inequality has been at once deeply embedded and difficult to fully identify,” she writes. “Making visible its full scope and the broad range of those invested in it is, even today, the first step to challenge it.” — Ellen Livingston

“Inequality has been at once deeply embedded and difficult to fully identify.” Ansley T. Erickson, Assistant Professor of History & Education

Reality Pedagogy 101

A crash course in teaching black youth

Urban schools “replicate colonial processes,” writes Christopher Emdin, TC Associate Professor of Science Education, in For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood…and the Rest of Y’all Too (Beacon Press 2016). Just as white teachers forced students in the first schools for Native Americans to assimilate, urban public school teachers compel black students to be “complicit in their own miseducation” and “celebrated for being everything but who they are.” Choosing between their own culture and academic excellence, students suffer “a loss of their dignity and a shattering of their personhood.”

“Neoindigenous,” Emdin’s term for these urban youth, signals why traditional classroom methods stifle learning and damage their emotional and academic well-being. His alternative: reality pedagogy, which meets “each student on his or her own cultural and emotional turf.” Students help determine how the class is managed, sometimes teach and are empowered to make the classroom familiar through everything from slang and graffiti to elaborate handshakes. These methods — informed by church services, rap circles and hip-hop battles — may contradict teachers’ training. Yet by displacing fear with understanding, Emdin suggests, and by immersing themselves in students’ culture rather than the other way around, teachers will transform classrooms into spaces where brilliance shines. — Robert Fuller

“Neoindigenous,” Emdin’s term for urban youth, signals why traditional classroom methods stifle learning.

Published Wednesday, Nov 30, 2016