“Opt Out” Movement Has High Visibility, But Not Necessarily Strong Support

While most Americans have heard of the “Opt Out” movement, less than one-third of Americans support it, and most people misunderstand the motives of parents who refuse to let their kids to take standardized tests in public schools, according to How Americans View the Opt Out Movement, a new, national study released on August 9 by Teachers College. The study is the first comprehensive look into public engagement with the Opt Out movement.

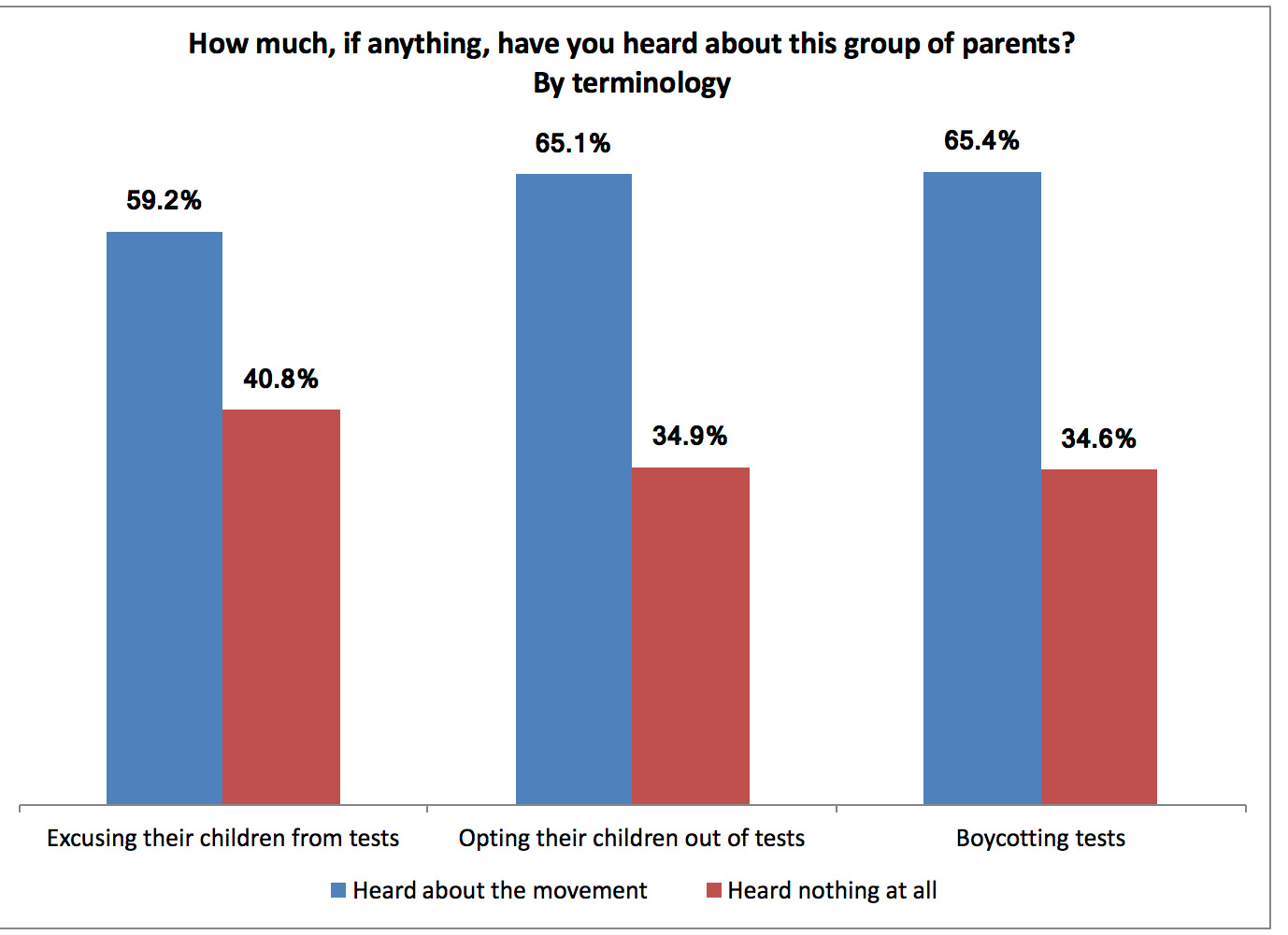

The online surveys of more than 2,000 respondents, led by Oren Pizmony-Levy, an assistant professor of international and comparative education studies, and co-authored by Benjamin Cosman (M.A. ’17), a consultant with the research and policy support group at the New York City Department of Education, were conducted in English in February and May 2017. The surveys used an experimental design in which respondents were randomly assigned to three equal-size groups. The first group was asked about parents “excusing their children from state standardized tests,” the second about parents “opting their children out of state standardized tests,” and the third group about parents “boycotting state standardized tests.”

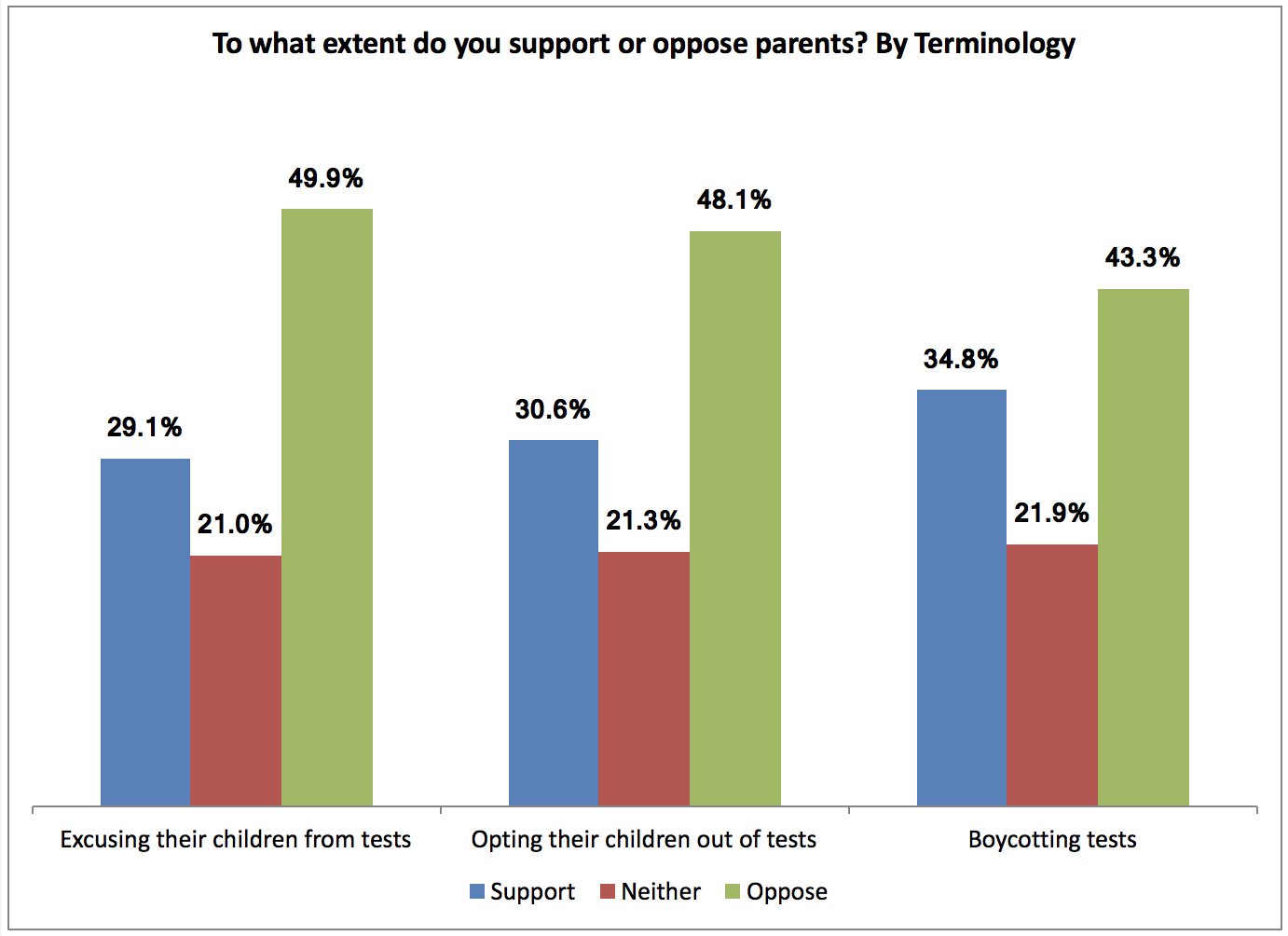

But recognition of the movement did not translate into overwhelming support. In another illustration that language matters, more than one-third of respondents (35 percent) said they supported the parent “boycott,” while only 29 percent supported “excusing their children” from testing, and 30 percent supported “opting their children out” of state tests (see Chart 2).

“We found modest impact of the wording on public opinion,” Pizmony-Levy said. “The key lesson here is that the public tends to support opt out parents when the parents are described in a meaningful or even political way. The parents are not just excusing their children from taking a test, they do that for a political or ethical reason and that is something the public seems to support or appreciate.”

The high level of public awareness of the Opt Out movement is a sign of how important standardized testing has become to education stakeholders, Pizmony-Levy said, as testing claims increasing shares of school districts’ budgets, curricula and instruction time.

“As a cornerstone of federal education policy in the United States, it is not surprising that standardized testing is at the epicenter of an emerging educational social movement, such as the Opt Out movement,” Pizmony-Levy and Cosman write. “Sociologists have long argued that social movements emerge against the backdrop of the modern centralized nation state.”

The study also found that:

- In the sample of the general public, 47 percent said they believed opting out reflected parents’ opposition to the Common Core State Standards and 45 percent said parents are motivated by the negative impact of standardized tests on teaching and learning, while 41 percent said they believe standardized tests force teachers to teach to the test. More than a quarter (27 percent) suggested that parents take part in the movement because their children do not do well on standardized tests.

- But opt out activists themselves cited different reasons for participating. A survey last year of opt out activists by Pizmony-Levy and researcher Nancy Green Saraisky found that the top three reasons for participation in the movement are: (1) opposition to evaluating teachers in part by their students’ test scores (37 percent), (2) a belief that standardized tests force teachers to narrow the curriculum to only the subjects covered on the tests (34 percent), (3) opposition to the growing role of corporations in schools (30 percent). Only 26 percent of opt out activists said they oppose the Common Core State Standards. "These findings are important because they suggest that the general public would be more supportive of the Opt Out movement if it truly understood the issues at stake for parents who opt out," Pizmony-Levy said.

- When ask why they support parents who take part in the movement, some respondents said they doubted whether the tests effectively gauged student learning, and some said they “believe in parents’ right to decide how to educate their children.”

- Opponents of parents who participate in the movement “stressed the importance of standardized tests to individual students and the general public and policy makers, and they emphasized the professional authority of educators and schools,” the study says.

- Despite criticism of the movement as mainly white, middle-class and suburban, Pizmony-Levy and Cosman found no demographic variations in support except for gender. Women showed a higher level of support than men for parents who participated.

“The Opt Out movement also teaches us something about the changing nature of media and sources of information,” Pizmony-Levy said. “The general public and the opt out activists draw on different sources of information about the movement. The public gets information from traditional media, and opt out activists get information from social media like Facebook and Twitter. These sources provide quantitatively and qualitatively different information. That’s why the public has such a different perception of the motivations that drive the Opt Out movement.”

Related Links:

Published Tuesday, Aug 8, 2017