TC Mourns Shakespeare Teacher John Henry Browne, a “True Keeper of the Flame”

“As a teacher educator, John mentored aspiring teachers in an office adorned with Shakespearean keepsakes,” recalled a memorial notice in The New York Times co-authored by Browne’s longtime TC colleagues Erick Gordon and Kerry McKibbin, with input from many of Browne’s friends and his family. “He modeled the timeless art of teaching literature and reading and had the uncommon ability to focus completely on the needs of the person before him.” [Read a remembrance by Gordon.]

“Failing to acknowledge a student’s individual response is usually tied to the teacher looking for the answer he or she already has in mind.”

At TC, Browne was best known for his “Teaching of Shakespeare” course, in which, on day one, he directed his students to select Shakespearean put-downs from a hat and then walk around class insulting one another. That exercise was but one reflection of Browne’s emphasis on teaching the Bard’s works through classroom performance -- an approach he developed after a National Endowment for the Humanities grant took him with a group of fellow teachers to Stratford-on-Avon during the late 1990s, where they watched 11 plays in 14 days.

“There was a lot of discussion, but what’s interesting is how most of that is very vague now; what’s real to me are the plays we saw,” Browne recalled in a 2006 profile by TC alumna Diane Rosen, published by the College’s Student Press Initiative. “That’s why performance is so effective in the classroom, it reinforces the learning so it stays with you. If you’re in a group and you’re rehearsing and deciding how to present something, it’s a natural process that can be enjoyable, that physicalizing the language. It’s a way to create understanding and be true to the material, which is a script.”

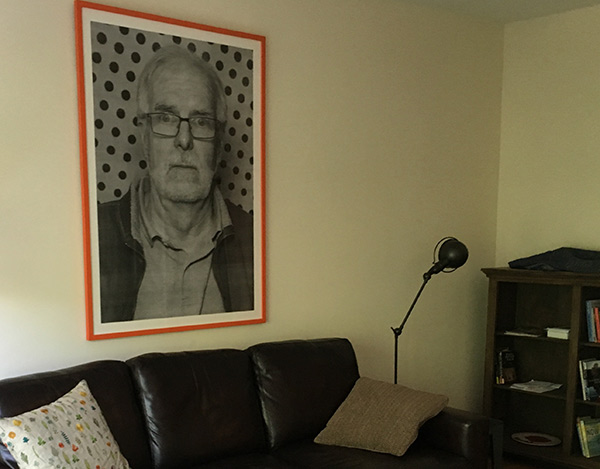

In another piece about Browne, published on the web right after his death, current TC doctoral student Adam Wolfsdorf recalled just how far Browne would go to “physicalize” literature. The setting was the good professor’s classroom, where Wolfsdorf and Browne – who, at six-feet five inches, with a high forehead and piercing blue eyes, bore a more than passing resemblance to the comic actor John Cleese -- were about to enact a scene between Iago and Othello:

“Professor Browne pulled me over into the corner of Thorndike 127 and whispered into my ear, ‘When I say ‘if thou dost love me, show me thy thought,’ I’m going to grab you by the throat and slam you into the wall,’” Wolfsdorf writes. “Like with most things John Browne, I figured he was f***ing with me.”

But sure enough, when the moment came, Browne “literally grabbed me by the throat, squeezed his fingers, and pushed me backwards. I felt my shoulders slam into the wall. For all of his plentitude of Irish wit and good humor, John believed in the absolute authenticity of the theatrical moment. I should have known better than to doubt him, if for no other reason than I believed in it, too.”

“Living life is what literature is about; it’s about the fact that we live, we die, and what happens in between is rather mysterious.”

John Henry Browne (even the name suggests a figure from Shakespearean times) was a Bronx native. His father was an alcoholic who spent years in and out of de-tox. His mother, a teacher, held the family together. Browne attended Catholic school, which left him with memories of nuns slapping students to extract confessions to classroom crimes.

“Given the Catholic rigor of hellfire and brimstone, religion for me was all about fear,” he told Rosen. “Not until I was in college, reading from Saint Paul about Christ offering love and reconciliation, was fear offset by another view. I can still remember thinking, ‘where have I been? I’ve never heard this before!’”

“We’re always misjudging,” he said. “You get a kid who’s not doing this, that, or the other thing, and then you find out his grandmother or his mother just died. For me, having an alcoholic father was a terrible secret, though, of course, everybody knew about it. And I’m not saying that when I was in high school, I would have wanted people to say, ‘John Browne’s father is a drunk, let’s not ask him to do much.’ But it would have been nice if once in a while a teacher had said, ‘Well, you had a rough time, so here, you can hand this in late,’ or ‘It will be OK.’”

Browne discovered Shakespeare at age nine, when an uncle took him to see a summer stock performance of The Merchant of Venice in a barn in upstate New York. After attending Hunter College, he enrolled in the English education doctoral program at NYU, taking night courses while working a day job in what was then New York City’s Welfare Department. He quit the former because the latter made academia seem irrelevant. With the war in Vietnam at its height, he tried to enlist in the Air Force, but was rejected because, despite his height, he weighed only 156 pounds. Instead, at his mother’s recommendation, he completed a six-week intensive teacher training program and took a job at Junior High 22 in the South Bronx, where, as a tall male, he was assigned all of the bottom level classes. He subsequently moved to the High School for Art and Design, where he taught for 28 years while also serving as an adjunct professor at LaGuardia Community College.

“I think not finishing my doctorate was a good thing for me, because if I had, and ended up teaching at a small liberal arts college, I don’t think I’d have been much of a teacher,” he reflected in Rosen’s profile. “Having to deal with adolescents was a real avenue of self-development that I wouldn’t have had in the closed world of academia.”

“I think in life I’m more pessimistic, but at least in the classroom, I’m optimistic. Classrooms are some of the last places where you can create a real sense of community.”

Adding that “no one is a natural teacher, born to spend their life in a room with adolescents,” he ruefully described his own early tendency to steer classes toward the “right” answer: “Those students probably don’t have the vaguest recollection of reading Madame Bovary because I was doing all the work. And it was my truth and not their truth.”

Later, he would adopt a far less didactic approach:

“It’s not me up there expounding, it’s the students talking, and I rely on that. My students are engaged and they are interesting, they have ideas I’ve never thought of. When I throw out a question, it really is genuine. I don’t know. I have my particular view, but I’m able to hear other views and then maybe alter mine…Failing to acknowledge a student’s individual response is usually tied to the teacher looking for the answer he or she already has in mind.”

With that outlook, it was perhaps not surprising that Browne was adamantly opposed to the various formulas that have been put forth to evaluate teachers, most of which give heavy weight to students’ performance on standardized tests. In 2011, he published a letter in The New York Times – and subsequently appeared on television – defending one of his former Teachers College students, Stacey Isaacson, after she was ranked in the 7th percentile of New York City teachers despite glowing reviews from her principal and former students.

Calling Isaacson “an extraordinary person and an exceptional teacher,” Browne declared that “to deny her tenure would be a bizarre injustice. George W. Bush had his ‘Texas miracle’ in education, which proved to be a fraud. Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg and former Chancellor Joel I. Klein had their testing-scores miracle, which has been proved to be just as false. Unfortunately, Secretary of Education Arne Duncan has followed their lead with misleading promises. The result is technocrats at the helm, and teachers’ voices silenced.”

Browne received a raft of honors for his teaching, including a 1993 award as Outstanding Adjunct in the English Department at LaGuardia; a 1998 Educator of Excellence Award from the New York State English Council; five Outstanding Teaching Awards from Teachers College; a Manhattan High Schools Teacher of the Year award in 1999; and designation as an Educator of Excellence, New York State English Council. But he was proudest of being asked to give the commencement address the year he left the High School for Art and Design. It was, perhaps, the most fitting of tributes.

“They say that all the world’s a stage, and that every man must play his part. John’s was a good part,” writes Wolfsdorf, who this summer will take over Browne’s “Teaching of Shakespeare” course. “He was not necessarily the lead actor – there were certainly professors and Shakespearean scholars globally who received more recognition and public acclaim than he – but John’s part was essential. His tremendous love for Shakespeare, and his humility before the genius of the bard made him the ideal mentor for so many students, over so many years. He was a true keeper of the flame, using his classroom to ensure that iambic pentameter, Macbeth, the sonnet, and Stratford-upon-Avon remained alive and fresh.”

In his own tribute to his mentor, Wolfsdorf recalled that he had recently sent Browne a tee-shirt covered with Shakespearean insults. Brown replied, “This is really cool, you ‘lump of foul deformity’… Your shirt makes such a ‘canker-blossom’ closing prop that rather than being a sort of ‘poisonous hunch-backed toad,’ it works to thread everything together. Also, and most of all, I appreciate the kindness, thoughtfulness, and concern this ‘rampallian! fustilarian! so well represents.”

Wolfsdorf, in turn, tells his departed teacher, that “If there were curtains, John, we’d ask for an encore.”

“’Out, out, brief candle!’” concluded the Times notice, quoting Macbeth. “You will be forever deeply missed.”

John Browne is survived by his daughters, Alison Browne Beckman and Gillian Browne; their mother, Lucille Browne; sons-in-law Craig Beckman and Brian Colavito; granddaughter Lilah Rose and Kaela Brynn; and his partner, Jonna Semeiks. Contributions may be sent to TC Fund in memory of John Brown to aid scholarships for students in need.

The Wit and Wisdom of John Henry Browne:

“To sustain yourself, you need to laugh. Humor lets some light in, it breaks down some of the overwhelming seriousness. That’s probably why people who’ve been oppressed often have a very good sense of humor, like African-Americans, the Jews and the Irish.”

“It’s extremely important for kids to know that you value them, like them. The hard part is that this can’t be accomplished with words alone, it has to be shown by who you are. Part of that is being organized and requiring things. It’s not about saying, ‘come, let’s all hug each other,’ but knowing that when they enter the classroom someone is serious about what they’re doing, someone cares about who they are.”

“Living life is what literature is about; it’s about the fact that we live, we die, and what happens in between is rather mysterious. And in very broad terms, it’s about constantly exploring what it means to be human beings.”

“You want to be what you can be for [students] at that moment, within the boundaries and limits of your role. Above all, you want to be a transparent human being whose humanity they recognize and respect, but that’s something you earn by what you do.”

“I think in life I’m more pessimistic, but at least in the classroom, I’m optimistic. Classrooms are some of the last places where you can create a real sense of community.”

Published Monday, Feb 13, 2017