Teachers College Study: Gap Between Refugee Policy and Practice Hinders Urban Refugee Children’s Access to Education

As a majority of the world’s displaced people settle in urban areas, TC researchers recommend ways to improve access to education for urban refugees

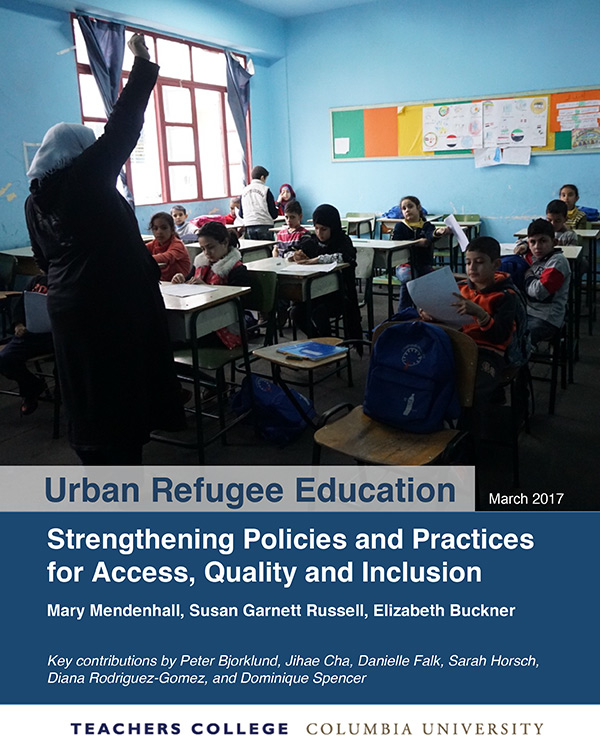

The report, titled “Urban Refugee Education: Strengthening Policies and Practices for Access, Quality, and Inclusion,” is the first-ever global study of urban refugee education. Funded by the U.S. State Department Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration, it documents the lack of access to schools and other educational and support services for displaced children as a majority of them have settled in cities and urban areas rather than clustered in camps.

[ A summary and the full report are available at tc.columbia.edu/ure2017. ]

“The emblematic image of refugees living in camps is no longer the norm,” according to the report, written by Mary Mendenhall, Assistant Professor of Practice; S. Garnett Russell, Assistant Professor; and Elizabeth Buckner, Visiting Assistant Professor, all in the International and Comparative Education program at Teachers College.

The Teachers College team interviewed 190 respondents working for UN agencies, and international and national non-governmental organizations (NGOs), in 16 countries across the Middle East and North Africa, Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Asia. They conducted additional, in-depth case studies in Nairobi, Kenya; Beirut, Lebanon; and Quito, Ecuador.

The report exposes a gap between policy and practice when it comes to ensuring access of displaced children to educational services in urban settings.

The Teachers College researchers make the following recommendations:

- Better coordination is needed between local, national and international organizations involved in educating refugee children.

- Displaced and immigrant students should be fully integrated and included in local and national schools, in programs that benefit both the refugee and host communities. Doing so would encourage host communities to be more welcoming of displaced students.

- In addition to increasing access to formal schooling, the authors write, “civil society organizations need to support the provision of non-formal education programs to fill the needs and gaps not met by government schools,” such as “psychological and social issues, skills development, language support, combatting discrimination and xenophobia, and academic support for lost years of schooling.”

To study access to education for urban refugees, the TC researchers began with United Nations data that paint a new portrait of the global refugee crisis in which:

- More than half of forcibly displaced persons are under 18, many of them unaccompanied minors

- More than 60 percent of refugees live independently in dense urban areas rather than together in the more iconic “tent cities”

- Only half of all primary school-aged refugees, and 22 percent of secondary school-aged refugees, are enrolled in school. Only 1 percent of all refugees have access to higher education.

- According to the U.N., of the 65 million forcibly displaced people across the world, most remain within their own countries. Fewer than a third, or 21 million refugees, have crossed national borders.

- While much attention has been paid to refugees going to westernized, developed countries, the vast majority of refugees—86 percent—reside in poorer countries in the “Global South.” Most move to a new location within their own country or to a neighboring country. Because of this trend, the burden of hosting displaced people falls on countries with the least resources. For example, Turkey is currently hosting 2.5 million Syrian refugees.

Documented or not, all displaced people under 18 have a right to attend school in their host communities, according to the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child. But the researchers found that the trend toward living independently, dispersed and embedded across dense metropolitan areas, makes displaced children vulnerable to the same problems faced by native urban poor children in attending school: over-crowded local schools, inadequate resources and teacher training, far distances and lack of safe transportation to and from school. As outsiders, they are often more vulnerable to xenophobia and discrimination by the host community.

And because global conflicts are lasting longer, the average duration of displacement for refugees is now 20 years, suggesting that tens of millions—entire generations of a conflict-ridden country—are coming of age in exile, or returning to their home countries without education or skills to support themselves and their families, the authors note.

The problems in educating displaced children are often more a matter of policy implementation rather than the policy itself, say the researchers. They found that, while the majority of the countries they studied “have relatively inclusive national policies that allow urban refugees to go to school, national and local governments are often unable to monitor educational quality [and] make information about policies available at the local level.” In addition, autonomy of local education and government authorities allows for “nonexistent, unclear or contradictory policies” at the local level, as well as “shifting and volatile policy environments, and misalignment between and across government offices.”

Visit TC.edu/URE2017 for additional resources on urban refugee education. An executive summary of the report is available at TC.edu/URE2017/summary, and the full policy report at TC.edu/URE2017/report.

The study was funded by the State Department Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration.

Published Friday, Mar 3, 2017