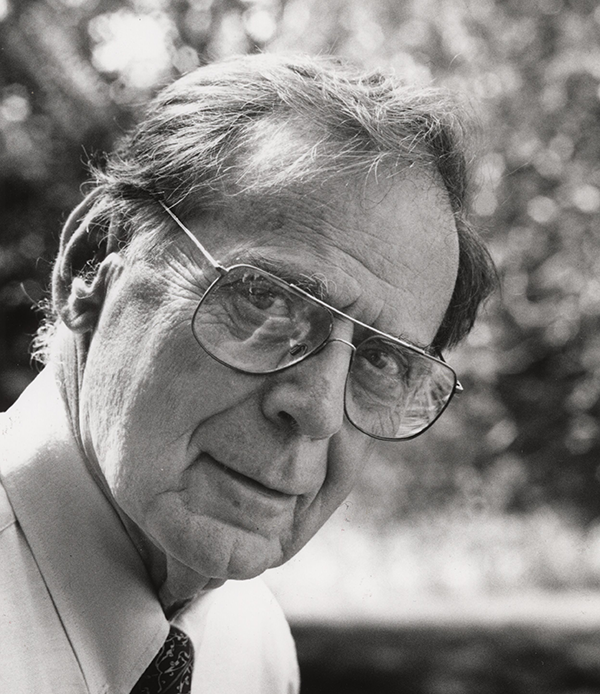

Morton Deutsch, Pioneer in Conflict Resolution, Cooperative Learning and Social Justice, Passes Away at 97

“We live in a highly individualistic society,” Deutsch said in accepting the 2006 James McKeen Cattell Award of the Association for Psychological Science. “Its ethos is that of the lone, self-reliant, enterprising individual who has escaped from the restraints of an oppressive community so as to be free to pursue his or her destiny in an environment that offers ever-expanding opportunity to those who are the fittest. I think this image has influenced much of American social psychology, which has been too focused on what goes on in the isolated head of the subject with a corresponding neglect of the social reality in which the subject is participating.”

[ From the The New York Times: Morton Deutsch, Expert on Conflict Resolution, Dies at 97 ]

Deutsch’s signature achievements include a landmark study of group tension and racial attitudes credited with helping to end legally sanctioned racial segregation in the United States; social experiments demonstrating that people will use opportunities to apply threats in competition, leading to a lack of cooperation; an acknowledged influence on Cold War negotiations and the peaceful transition of Poland to non-Communist rule in 1989; and a score of influential books, including Interracial housing: A psychological evaluation of a social experiment (1951, with M.E. Collins); the landmark The Resolution of Conflict: Constructive and Destructive Processes (1973); and The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice, co-edited with TC psychologist Peter T. Coleman and alumnus Eric Marcus, considered a bible of the field.

MAKE A GIFT

“An individual with Morton Deutsch’s theoretical brilliance comes along maybe two or three times a century,” said David W. Johnson (Ph.D. ’66), a former TC student of Deutsch’s who is now Professor of Educational Psychology at the University of Minnesota.

At Teachers College, Deutsch founded the International Center for Cooperation and Conflict Resolution (since renamed for him, but known as ICCCR). He retired in 1990 as Edward Lee Thorndike Professor Emeritus of Psychology and Education, but continued to run the Center for nearly a decade and remained active up until his death, authoring more than 50 additional papers or book chapters during that time. Deutsch mentored nearly 70 Ph.D. students at TC, including many current leaders in the fields of conflict negotiation, peace studies and mediation.

“American social psychology has been too focused on what goes on in the isolated head of the subject with a corresponding neglect of the social reality in which the subject is participating.”

—Morton Deutsch

“We were all so influenced by his way of thinking through problems, his approachability and his encouragement of students’ creativity as he helped us clarify and critique our thinking,” said Roy Lewicki (Ph.D. ’69), Irving Abramowtiz Professor of Business Ethics Emeritus at Fisher College of Business at The Ohio State University. “We also absorbed his commitment to action and working for social justice.”

In a message to the Teachers College community, TC President Susan Fuhrman wrote that “with the passing of Morton Deutsch, Teachers College and the world have lost a giant – a brilliant and pioneering scientist whose ideas have changed history, an electrifying and beloved teacher who has mentored generations of students, and an extraordinary human being who inspired hope and served as a powerful force for good.” Fuhrman called Deutsch “an irreplaceable figure in our own and the global community – a scientist whose commitment to social justice embodied Teachers College’s mission. We mourn his loss, but take comfort in the fact that his work is being carried forward by the countless students and scholars who today continue to be influenced by his ideas.”

[ Honor Morton Deutsch’s memory by contributing to The Morton Deutsch Endowed Fellowship Fund, which provides ongoing support for students in TC's Social & Organizational Psychology program who are studying conflict resolution. ]

Concern for the Underdog

Morton Deutsch was born on February 4, 1920 in New York City. As a Jew, and as the youngest of four brothers, in his neighborhood group and in his class at school, he was frequently in a position of low power.

“I was aware of the dangers introduced by atomic weapons, and I was aware of the UN Security Council, which had been newly formed. I had an image of them either cooperating or competing and had different senses of what the consequences would be for the world.”

—Morton Deutsch

“I've always been concerned about the underdog, and the people who are stepped on,” he recalled in an interview with the Teachers College Oral History Project in 2009.

At age 15, he enrolled in the City College of New York, where students and faculty alike were highly politicized. “In the Alcove – the lunch room – in one corner there were people who represented the first International, then the second International, then the third and the fourth,” he recalled. “So at City College you became pretty good at articulating Marxist ideology and Marxist criticisms.”

Deutsch subsequently earned an M.A. in 1940 from the University of Pennsylvania and planned to become a psychoanalyst. But after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he joined the Air Force, became a navigator and flew in some 30 combat missions over Nazi Germany.

“Being in World War II and experiencing the devastation and horror of war, even though I felt the war against the Nazis was justified, I became interested in prevention of war,” Deutsch told TC Today magazine in 2009.

[ Read President Susan Fuhrman's message to the Teachers College Community ]

A Practical Theory

After the war, Deutsch earned his Ph.D. at MIT under Kurt Lewin, a pioneer in the fields of social, organizational and applied psychology whose dictum was “There’s nothing so practical as a good theory.” Lewin brought “a combination of science and concern for social issues to the study of human interdependence,” Deutsch later recalled.

Working in Lewin’s newly founded Research Center for Group Dynamics, Deutsch wrote a dissertation that compared the psychological effects and productivity of five-member groups that were either cooperative or competitive. The model for these groups was the five-member United Nations Security Council.

“Violence and war are potentials of humans, but they are not inevitabilities. The view that human nature is inherently evil and must end in violence is a false view that encourages its falseness to become true.”

—Morton Deutsch

“Just before I resumed graduate studies, there were the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” Deutsch told TC Today. “So I was aware of the dangers introduced by atomic weapons, and I was aware of the UN Security Council, which had been newly formed. I had an image of them either cooperating or competing and had different senses of what the consequences would be for the world.”

Deutsch’s five-member groups in his research consisted of students in courses he was teaching at MIT. In one group, he gave everyone the same grade based on the group’s overall performance, while in another, he graded on a curve for individual performance. He found that the students graded for their cooperation not only seemed to form better relationships with one another, but also to learn better. The field of cooperative learning, subsequently developed in great part by Deutsch’s TC student David Johnson, grew out of this work.

More broadly, Deutsch’s dissertation was the first iteration of his Theory of Cooperation and Competition, which holds that the dynamics and ultimate success of a group depend on the extent to which group members believe their goals are shared and thus see a potential to make common cause. Presented in a paper in 1949, the theory argues that the social processes and personal relations that occur in groups are affected by three group processes: substitutability, or how a person's actions are able to satisfy the intentions of another; cathexis, or individuals’ disposition to evaluate themselves or their surroundings; and inducibility, or the readiness of an individual to accept the influence of another person. Conflict itself could be “a source of psychological growth” with “a lot of positive effects if it’s done well,” Deutsch argued, but “destructive conflict, where you're trying to defeat one another, often leads to real psychological harm.”

While working at Lewin’s Center in Cambridge, Deutsch also had occasion to supervise the work of a young woman named Lydia Shapiro. He fired her, he later wrote, after “learning that she spent much of her time sunning herself on the banks of the Charles River.” They were married a year later.

“In moments of marital tension, I have accused Lydia of marrying me to get even, but she asserts it was pure masochism on her part,” Deutsch wrote in a chapter in a book dedicated to his work. “In our 60 years of marriage, I have had splendid opportunities to study conflict as a participant observer.”

[ Watch full interview with Morton Deutsch as part of the Teachers College Oral History Project ]

Prejudice and Distributive Justice

In 1951, Deutsch coauthored a comparative study of interracial public housing projects in New York City and Newark, New Jersey. At the New York City sites, blacks and whites lived in the same buildings; the Newark sites were segregated by building. “It was clear that the two types of projects differed profoundly in terms of the kinds of contacts between the two races and the attitudes they developed toward each other,” Deutsch later wrote. Published in 1951, the research prompted the Executive Director of the Newark Public Housing Authority to declare that “the partial segregation that has characterized public housing in Newark will no longer obtain.” Deutsch himself went on to become active with The Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues’ committee on inter-group relations, which contributed materials that led to the U.S. Supreme court’s 1954 decision striking down segregation in the public schools.

“It's very hard to produce a coherent democracy that isn’t co-opted all over again. Have a sense of the time it takes, and having people who are really committed over a sustained period to help move the group to real democratic participation, is really essential.”

—Morton Deutsch

In 1956, now on staff at the Bell Telephone Laboratories, Deutsch, with Robert M. Krauss, conducted an experiment called the Acme-Bolt Trucking game. In the game, players operating two trucking companies, Acme and Bolt, earn money by sending their trucks along a short route that they share and lose money when they follow separate longer routes. At one juncture along the short route, there is room for only one truck to pass at a time. In some variants of the game, both players possess weapons in the forms of gates that can be used to force the other player to follow the longer route; in others, only one player possesses the gates. Through Acme/Bolt and subsequent scenarios, Deutsch and others have shown that the introduction of weapons into negotiation situations heightens conflict by tempting the participants to use those weapons to press for advantage, and that negotiations increasingly become zero sum, with both sides aiming for complete victory and the complete defeat of the other side.

A broader canvas

During the Cold War, Deutsch became one of a small group of psychologists who spoke frequently with officials from the U.S. Departments of State and Defense. In 1961, at the height of the Berlin Crisis (triggered by the Soviet Union’s ultimatum to the Allied powers to leave West Germany, culminating in the building of the Berlin Wall), the American Friends Service Committee held a meeting in Capacon Springs, West Virginia, devoted to a book co-edited by Deutsch, Preventing World War III: Some proposals. At the meeting, under Deutsch’s direction, the Deputy Soviet Ambassador and the American Undersecretary of State reversed roles, with each arguing for the other’s position.

“It was very interesting,” Deutsch recalled in his TC Oral History interview. “They were good at role-reversing. But the ambassadors from France and Poland said, ‘Yes, you may be saying what the other thinks, but you're not considering what we think.’"

In 1989, both Janusz Grzelak, a leading figure of the Solidarity movement in Poland, and Janusz Reykowski, a negotiator for the nation’s Communist Party of Poland, also cited Deutsch’s work as having played an essential role in the peaceful transfer of power from the Communist party to a democratically elected government.

In 1963, Deutsch joined the faculty of Teachers College to found a new social psychology doctoral program. In short order, he used grants from the National Science Foundation, the Office of Naval Research and the National Institute of Mental Health to establish his own laboratory, recruit a corps of doctoral students and begin exploration of factors that lead to cooperation or competition in complex negotiation situations.

In 1986 Deutsch founded TC’s International Center for Cooperation and Conflict Resolution (ICCCR) with the goal of integrating conflict resolution theory and real-world practice. The Center has since run workshops for superintendents and foundation leaders; trained teachers to deal with inter-student and gang violence in lower-income communities; and offered a New York State Certificate Program in Conflict Resolution and Mediation. Today, under the direction of Deutsch’s former student, TC Professor of Psychology and Education Peter T. Coleman, ICCCR has become widely known for its use of dynamical systems theory to study intractable conflict in regions such as the Middle East.

Since 2004, ICCCR has bestowed the annual Morton Deutsch Awards for Social Justice, the recipients of which include Michelle Fine, a leading scholar-advocate in social justice, Geoffrey Canada, founder of the Harlem Children’s Zone, and the social psychologist Claude Steele. Deutsch himself received a long list of honors during his career, including the Kurt Lewin Memorial Award; the inaugural Lifetime Achievement Award of the International Association for Conflict Management; the G. W. Allport Prize; the Carl Hovland Memorial Award; and the Teachers College Medal for Distinguished Service to Education. He also served as President of both the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues and the International Society of Political Psychology.

A faith in human nature

Even as the 21st century began with waves of violence around the world, Deutsch remained fundamentally optimistic about human nature. “Violence and war are potentials of humans, but they are not inevitabilities,” Deutsch said in 2013. “The view that human nature is inherently evil and must end in violence is a false view that encourages its falseness to become true. Interpersonal violence, such as murder, has decreased remarkably over the centuries. Unfortunately, weapons have become vastly more destructive, so it’s essential that we bring them under control.”

Success in doing so, he predicted, will depend in great part upon the recognition that “We're all human beings living in this unique neighborhood, our planet, in this universe. We share a common ancestry, a common environment and many common problems.”

Deutsch acknowledged the existence of “something very like evil in the world... people who are psychopaths and sociopaths.” But the bigger obstacle to peace, as he saw it, is often the impatience of those seeking to change the world for the better.

“It’s very hard to produce a coherent democracy that isn’t co-opted all over again,” he said in 2011, commenting on the wave of revolutions and uprisings in the Middle East and Africa. “Having a sense of the time it takes, and having people who are really committed over a sustained period to help move the group to real democratic participation, is really essential. It takes time, planning and effort.

“So – I cross my fingers and hope something good will develop.” – Joe Levine

* * * * *

Among the books that deal with Morton Deutsch’s life and work are Morton Deutsch: a Life and Legacy of Mediation and Conflict Resolution, by Erica Frydenberg, and Conflict, Interdependence, and Justice: The Intellectual Legacy of Morton Deutsch, edited by Peter Coleman. A special 2006 issue of the journal Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology was dedicated to Deutsch’s work.

On the TC web, read Giving Peace Education a Chance; Morton Deutsch: Bullish on Occupy Wall Street and Bottom-Up Peace, a joint opinion piece published by Deutsch and Coleman.

Published Wednesday, Mar 15, 2017