Hindsight, the saying goes, is 20/20.

It is one thing, then, to look back on how world-renowned scholars and athletes have channeled early failures into ultimate success, and quite another to think about using to failure to motivate underserved young women in nations around the world.

Yet Xiaodong Lin-Siegler believes the method can work.

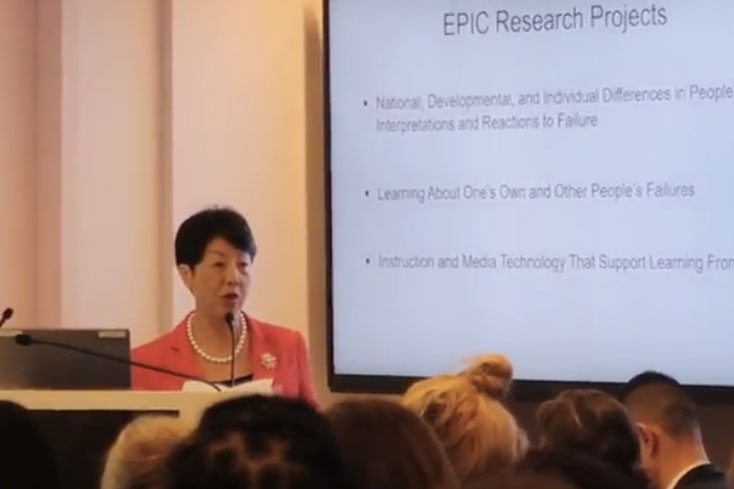

Earlier this week, in a keynote address delivered to The Population Council’s GIRL Center for Innovation, Research and Learning at the 74th Session of the United Nation General Assembly (UNGA 74), Lin-Siegler, Professor of Cognitive Science and founder of Teachers College’s Education for Persistence and Education Center (EPIC), shared her preliminary research findings on how people conceptualize and react to failure.

The inability of schools to emphasize that failure is in fact a “normal part of life” leads to students’ conception of “poor grades” as failure, Lin-Siegler said. "That young people are internalizing that message isn't surprising," she said — "but what's more troubling is that they are not seeing their poor understanding of concepts and instructional materials as the more important failure, or even as a failure at all."

Whereas elite athletes and scholars characterize early failures as ephemeral bumps along the road, the initial frustration born from an inability to grasp fundamental course materials can leave struggling students with negative emotions that they will carry into adulthood, Lin-Siegler said.

Failures are especially overwhelming to young adolescents. Yet, very few students know how to handle these negative feelings. This is a great opportunity for us as educators.

Xiaodong Lin-Siegler

“Everyone reacts negatively to failure or undesirable situations. Failures are especially overwhelming to young adolescents. Yet, very few students know how to handle these negative feelings. This is a great opportunity for us as educators because there has never been a class in the students’ lifetimes that has taught them how to deal with failure and negative emotions induced by the failing experiences. And that is a great opportunity for educators to help young people understand the value of failures: They offer us important information and opportunities.”

Lin-Siegler’s ideas were enthusiastically received, though her audience certainly appreciated the risks that accompany them.

“If we’re being honest, all of us in the field have incentives not to talk about failure,” said Stephanie Psaki, Director of the GIRL Center, which provides scientific evidence on population-related issues to the governments and policymakers globally. “We’re under constant pressure from donors in our community to present everything we do as a success. And because we are so deeply committed to making the world a better place for girls and young adolescence, we can also be wary of casting a critical eye on our own work or the work of others. It is often easier to take the path of least resistance. But there is so much to learn if we are willing to acknowledge what is effective and what is not effective. Our communities therefore demand of us a new approach. One that is data-driven, results oriented and approaches that empowers us to recognize when something we thought would work and not work, instead of delivering only successful stories.”

TELLING A BETTER STORY Lin-Siegler argues that students should be encouraged to create narratives around their own failures, partly as a way to distill positive lessons from those experiences.

Lin-Siegler’s work meets all of those criteria. In 2016, she and her students published the results of a study in which some high school science students learned about the multiple failures that Albert Einstein and other famous scientists experienced before achieving career-making breakthroughs in their research. The students earned significantly higher grades than peers who only learned about the scientists’ successes. The study, published in The Journal of Educational Psychology, made headlines around the world.

[Read the American Psychological Association's press release about the study and a story in The Atlantic about Lin-Siegler's work.]

Since founding EPIC two years ago with support from several high profile donors (the National Science Foundation; the Yu Panglin Charitable Trust; Weiming Education Group, based in Hong Kong; and the Alvin & Peggy S. Brown Family Charitable Foundations), Lin-Siegler has embarked upon a series of in-depth psychological interviews of sixth and ninth grade children, and of Nobel laureates and champion athletes. The latter include Simone Biles, Olympic medalist in gymnastics and Natalie Coughlin, Olympic medalist in swimming who asserted that she considers failure “almost like a blessing and like a learning opportunity,” adding “it forced me to make tough decisions.”

Students, too, should be encouraged to create a narrative around their own failures, Lin-Siegler said in her keynote address at the GIRL Center.

“Memory research on cognition tells us that if you can’t tell a good story about what has happened in the past, it means you have not learned from the experience,” she pointed out.

A panel discussion following Lin-Siegler’s address, with presentations by panelists Bitania Lulu Berhanu, an Ethiopian elementary school program designer; Manjula Singh, Program Director of the Children's Investment Fund Foundation in India and Nadia Naviwala, a senior advisor with the Citizens Foundation who has worked extensively on school reform in Pakistan.

Lin-Siegler, who also joined the panel, cautioned that failure, whether analyzed subjectively or in the realm of data-driven evidence, should always be placed and interpreted in context.

We need scientific data to really understand how different populations, nationalities, cultures and age-groups interpret and react to failure.

Xiaodong Lin-Siegler

“We need to understand how people in general interpret failure, as well as how different individuals from different cultures think about failure,” she noted. “For one girl, earning a grade of 65 points may be a tragedy and a big success for another. We need scientific data to really understand how different populations, nationalities, cultures and age-groups interpret and react to failure.”