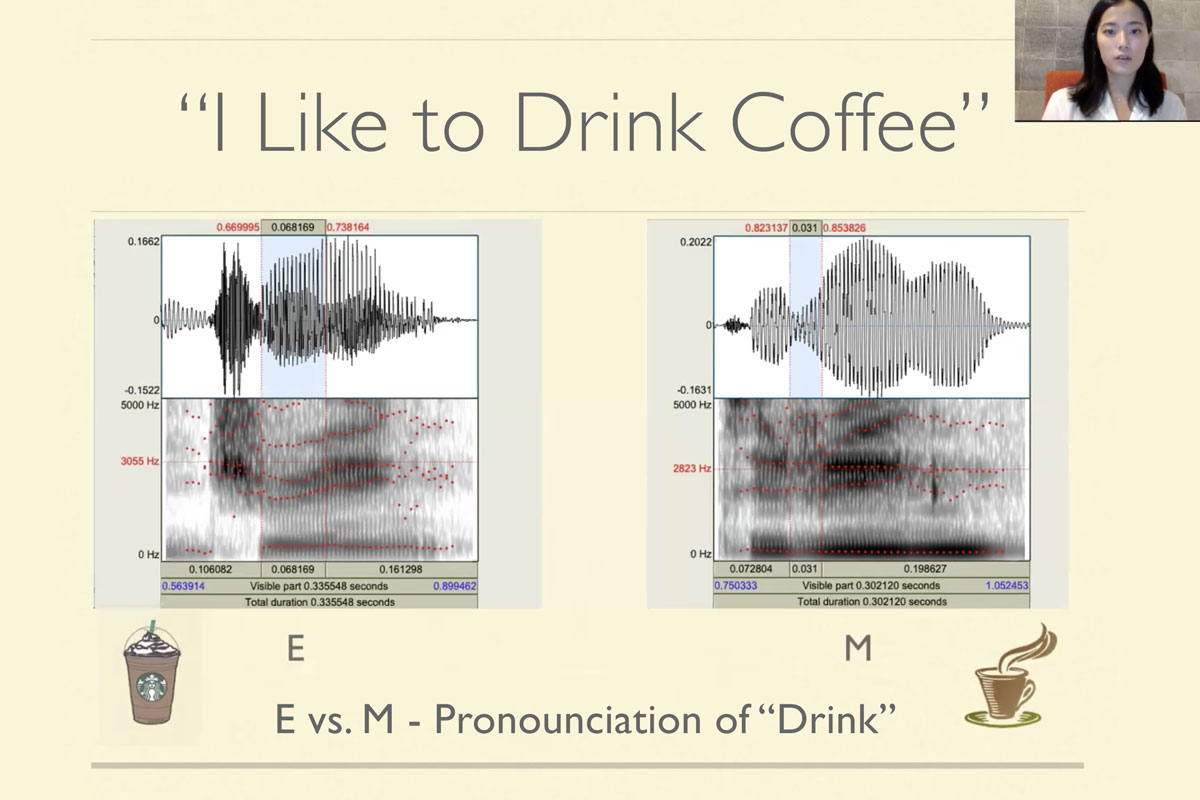

In a project that Erika Levy assigns in her online introductory Speech Science course, students record speech and create spectrograms — charts that visualize the energy expended in forming different sounds. Often the focus is on two very different speakers saying the same sentence: for example, in one student’s project, a young Korean woman who learned English at age 8 and an older Korean woman who learned it age 35, both saying, “I like to drink coffee.”

“I’m fascinated by the early childhood experiences that shape people’s speech,” says Levy, Associate Professor in Communications Sciences & Disorders and Director of TC’s Speech Production and Perception Lab.

Production and Acoustic Analysis

Speech Science Final Project by Eunice Hong

The speech comparison project, which helps students understand the speech acoustics and articulation that come into play in different languages and dialects, grew out of the period when Levy’s family lived in Vienna and Levy attended the American International School there. “I saw how very young kids would come in from different countries and flawlessly pick up English. But if they came in at age 12 or later, most would never lose their accents.”

By that point, Levy — herself a French, English, German trilingual — had already lost her own fluency (but retained her accent) in Czech. In 1971, her family had been given 48 hours to pack their things and leave what was then Czechoslovakia. Her father, an American journalist, was facing a prison sentence of 5,615 years (based in part on the number of times he had referred to Soviet President Leonid Brezhnev as “a swine,”), and Levy and her sister – young children at the time — had been declared spies.

My early experiences as a child are a big part of my motivation to help people to speak. Everyone should have the right to speak and be heard.

“My early experiences as a child are a big part of my motivation to help people to speak,” she says. “Everyone should have the right to speak and be heard.”

Levy, who was recently elected a Fellow of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, is an authority on the treatment of dysarthria, a motor speech disorder in which the muscles and/or control of the muscles that are used to produce speech are damaged, paralyzed, or weakened by an underlying neurological condition. One branch of her work focuses on testing treatments for adults with Parkinson’s disease. This summer, she published, in Lancet’s EClinicalMedicine, the first randomized clinical trial demonstrating that Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT LOUD), which trains people to speak at a more normal loudness level, improves intelligibility for American English speakers with Parkinson’s disease. With her doctoral students, she has performed related research on Mandarin and Spanish speakers with Parkinson’s disease.

ACCENTING THE POSITIVE Recent studies suggest that Levy's speech treatment for children with cerebral palsy, which is provided through the medium of play, may improve intelligibility with both English and French speakers (Photo: TC Archives)

Levy’s other work centers on children with cerebral palsy, an area of research that is still in its infancy. Over the past six years, she has developed a method she calls Speech Intelligibility Treatment, in which children are trained to “Speak with your big mouth and strong voice.” A key component of the treatment is that Levy and her master’s and doctoral students provide it through the medium of play, in an annual three-week summer speech camp she has run at TC since 2014. Recent treatment studies at Teachers College, as well as in Belgium, suggest that the method may improve intelligibility in both English- and French-speaking children with cerebral palsy.

[Watch a video about Levy’s summer speech camp for children with cerebral palsy.]

Given Levy’s up-close and personal approach to speech therapy, it’s not surprising that she has mixed emotions about teaching online.

She is keenly aware of the distance in “distance learning” — so much so, that whether her lectures are asynchronous or live online (and video-recorded), she concentrates very hard on speaking to her students as if they were there in the room. She also hopes to resume, online, her classroom practice of featuring guests such as Matthew Joffe, Director of Outreach and Education in the Wellness Center at LaGuardia Community College in New York City, who has previously lectured in her course on Neuropathology of Speech to describe how speech therapy has helped him to speak intelligibly despite his facial paralysis.

In the Speech Science class, we work asynchronously, using threaded discussion tools, and the students interact a lot. Though it takes self-control, I have been standing back more and letting them discuss questions that come up instead of jumping in, and that’s really a better way to teach.

Yet despite her emphasis on the visual, when it comes to understanding speech and its disorders “there’s something to just listening,” Levy says. “It really allows you to focus on the specific speech sounds and how they are produced and what might make them difficult to understand — whereas we can be fooled by looking at people and thinking we understand.”

Levy credits Veronica Thomas, Director of TC’s Office of Digital Learning, with identifying digital tools that could help her capitalize on the potential to have her students engage in such distilled listening online. For years of in-person teaching, Levy has instructed students on using PRAAT, the free software program for reconstructing and analyzing acoustic speech signals that enables students to generate spectrograms. Thomas helped her provide instructions to her online students so that they could record and present their speech comparison projects as videos with the spectrograms, sound files, and the students themselves narrating their projects. Levy finds herself impressed by the students’ skills and creativity every year. Thomas also helped Levy redesign her course websites to be more navigable and visually appealing.

[Read a story on how Thomas and ODL have been leading TC’s adaptation to digital teaching.]

“This summer, one of my teenage children started taking a class online, and when we looked at the website, we couldn’t figure out what was what,” Levy says. “It made me think about my own students’ experience. Veronica really made my site very systematic and welcoming.”

But perhaps the most positive change in teaching online, Levy says, is that she has learned to let students use their own voices more. “In the Speech Science class, we work asynchronously, using threaded discussion tools, and the students interact a lot. Though it takes self-control, I have been standing back more and letting them discuss questions that come up instead of jumping in, and that’s really a better way to teach.”

For Levy, it’s a lesson that harks back to earlier times.

“It’s so important listen to people with any speech ability from any country with open ears. Why can’t we just listen and understand?”