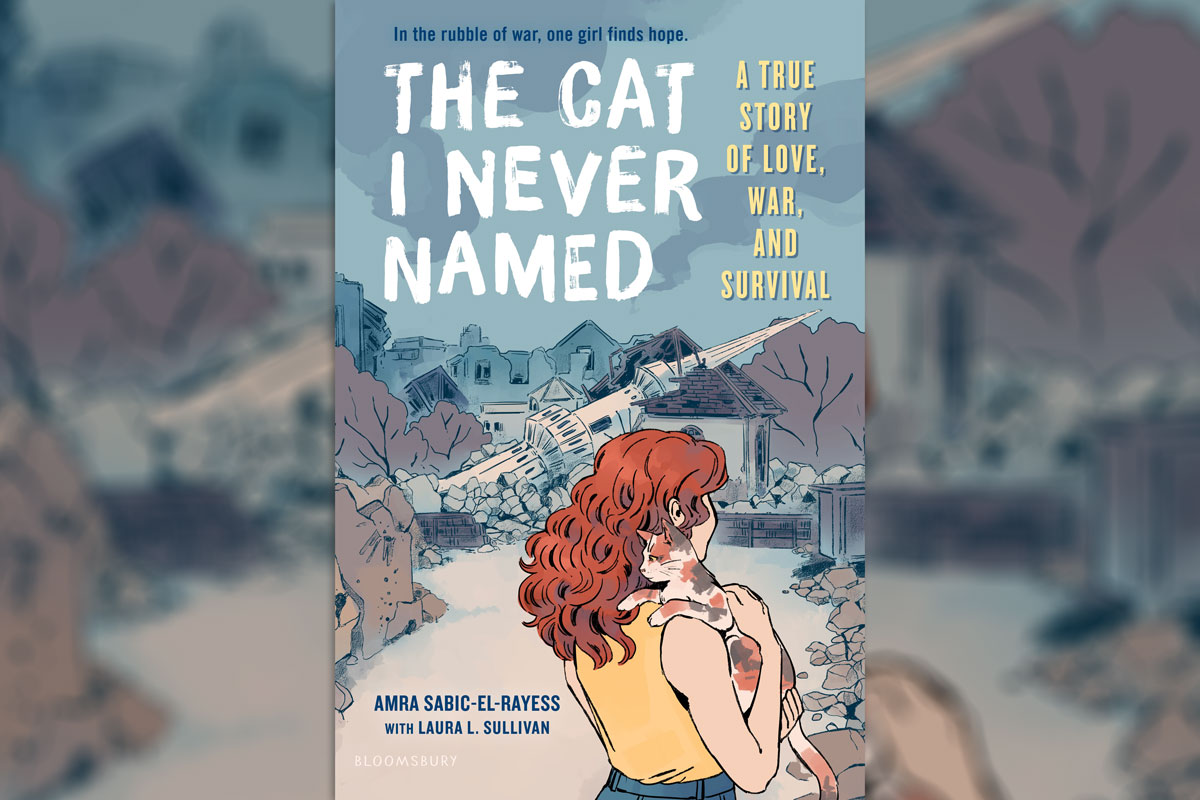

Near the beginning of The Cat I Never Named: A True Story of Love, War, and Survival, Amra Sabic-El-Rayess’s memoir of living through genocide as a teenager during the early 1990s in Bosnia and Herzegovina, teen-aged Amra walks with her father, the gentle and idealistic “Tata,” through their home city of Bihać. They have set out to pick up the beautiful cake Amra’s parents have ordered for her 16th birthday. It’s a weekend morning in spring, the sun is shining, the people Amra knows are out on the streets and her best friends are coming for a slumber party.

Certainly, there are ominous signs that trouble is at hand: Bosnia and Herzegovina has recently declared independence from “the cobbled-together nation of Yugoslavia,” and there is news from Belgrade and elsewhere that Serb soldiers are harassing and harming Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) — even secular Muslims like Amra and her family.

But on this lovely morning, Tata offers his daughter his arm “like an old-fashioned gentleman” and Amra’s universe still seems to be a place in which getting straight A’s matters most and, as her parents believe, “humankind is fundamentally good…wars are mistakes, violence just a blip on the road to universal humanity…the world will come to its senses and be the peaceful, philosophical, intelligent place it was meant to be.

Amra Sabic-El-Rayess reads from The Cat I Never Named

“The news reports come back to me, things it was easy to overlook for so long because they were adult affairs, paling in comparison to my own concerns,” Amra the narrator reflects in hindsight. But “there is always bad news, right? Announcers don’t look into the camera and tell us cheerfully that many children are happy and healthy, that cities are safe and people well fed. No, they tell us that some city was bombed, some politician assassinated. And if by chance people are at peace, they speak of hurricanes and mudslides, of fires and famine. The news is never good news. But this is home. Somehow, I never truly associated news of the breakup of Yugoslavia with my peaceful city.”

Alas, that illusion does not survive the day, or even the length of their walk. Amra and her father encounter refugees in double sets of clothes. Tata “hands out money to everyone he sees until he has no more money.” And then the tanks of the Yugoslav National Army roll through the streets in a show of force. A soldier “spits in the road in my direction, and I am left in the dust and fumes the tanks belch in their wake. The street is cracked and crumbled where they passed. I know how it feels. My heart feels the same.”

A soldier “spits in the road in my direction, and I am left in the dust and fumes the tanks belch in their wake. The street is cracked and crumbled where they passed. I know how it feels. My heart feels the same.”

Though a crossover into adult nonfiction, The Cat I Never Named (released officially this week by Bloomsbury) is written for young adults, and as a book in that category it does not scrimp on teen angst and romance, humor and details of life amid siege and deprivation. (We learn that a diet of onions can lower one’s blood pressure; that rosehip tea has enough vitamin C to stave off scurvy; that soap can be improvised from fat and ash.) The prose is lyrical rather than social-scientific: a row of linden trees is described as “very ancient with gnarled trunks, but strong and upright like proud old men.” Amra’s father “weeps easily…his feelings are like clouds, and when they become too heavy for him, they rain down on the world.” And bread is “the smell of home…of comfort… stability… unity” and home-baked brioche rolls “smell like sweet, yeasty heaven.”

But Sabic-El-Rayess, Associate Professor of Practice in Teachers College’s Department of Education Policy & Social Analysis, is, by trade, an observer of how societies hold together and fall apart. From the first, her memoir’s central topic is human nature, and the alternative reality in which those whom we know, love and trust become monsters, indifferent to our humanity and convinced — as a friend who betrayed Sabic-El-Rayess would later write to her unapologetically — that they are acting in the service of “a higher cause.”

“On a good day, some friend of a friend dies…on a bad day, a relative or close friend dies,” the narrator says. Yet, at another moment, she declares, “There can’t be mold, or sorrow, or despair in a world that has three newborn kittens in it.”

The question facing Amra, on the cusp of adulthood, isn’t simply whether she and the people she loves will survive, but also, whether she will emerge with her own humanity intact, and with a sense of connection to others that rises above the tribalism of “us” and “them.” That she does, despite witnessing horrific bombings and killings, learning that Serb neighbors were party to plans to assign her to a rape camp, and realizing that the United Nations, the United States and the rest of the world are indifferent to a genocide that is taking place in plain sight, owes in large part to a stray cat who adopts her family. The near-magical Maci (Bosnian for “cat”) repeatedly acts in ways that protect the Sabics from death and disaster, but it is her affection and loyalty that give Amra something good to hang onto in an increasingly twilit world in which, “on a good day, some friend of a friend dies…on a bad day, a relative or close friend dies.” [Read the scene in The Cat I Never Named describing the first meeting between Amra and Maci.]

In one scene, after trying (and failing) to will an attacking Serbian plane to reverse its course, Amra abandons hope and takes to her bed — only to discover that Maci has given birth under the blankets.

“There can’t be mold, or sorrow, or despair in a world that has three newborn kittens in it,” she thinks.

It is small epiphanies like these that give her the strength to continue her studies and risk her life to attend infrequently-held school. There are no textbooks and almost no paper to write on (people have used it all for fires to keep warm and cook), so each day Amra fills one of the “anemic little notebooks” provided by the UN, memorizes her notes, and erases them so she can use the pages again. But occupying her mind and being with friends is far better than a typical day of “staying home, behind shuttered windows, in an ice-cold house, being bored and hungry.”

Eventually she volunteers as a teacher and aid worker, and ultimately, aided by almost impossible luck, receives a scholarship that enables her to attend college in the United States. There the story ends, and we don’t get to see Sabic-El-Rayess transform, like an Anne Frank whose life is not snuffed out, into the full-fledged scholar, human rights advocate, teacher and mentor that she has become — though in the book’s afterward she draws sobering parallels between the Bosnia of her youth and American society today. (“Hate can make people commit horrific violence, such as Serbs raping my relative in a rape camp. Only hate is that powerful, and I see hate on the rise in the United States and around the world.”)

But Amra does survive with her humanity very much intact, and with a world view that reflects both her father’s hopes and her mother’s sense of realpolitik.

We like to see our enemies as fairy-tale villains, thoroughly wicked. But Tata sees nuances. He sees people, not causes or countries.”

“Tata talks about hard things. Right things, but hard things,” she reflects. “How can you tell someone whose children were killed by a bomb that the Serbs are human, that they are individuals who may hate the war as much as we do, or be ignorant of exactly what is happening, or even indifferent ... but not uniformly evil. We like to see our enemies as fairy-tale villains, thoroughly wicked. But Tata sees nuances. He sees people, not causes or countries.”

Perhaps the most important takeaway is one that Amra voices early on in this exchange with her father:

“Maybe bad people never believe that they are bad,” I venture. “While good people are always questioning their goodness. Maybe that’s what keeps them good—the constant questioning.”

“My wise daughter,” Tata says, pulling me into one of his famous loving hugs.