Swallowing and coughing are life-sustaining acts — the one, obviously, to ingest food and drink, and the other to prevent food, drink or anything else from going “down the wrong pipe.”

Both of these critical functions typically go awry in brain-based disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), stroke and some cancers of the head and neck. People with these conditions often lose their ability to cough vigorously and can end up aspirating food or liquid into their lungs, resulting in pneumonia that frequently proves fatal.

While research has shown that it is possible to improve cough function in Parkinson’s disease patients, little research has focused on Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP), the most common among a group of conditions collectively known as Parkinson-Plus Syndromes. PSP afflicts about 20,000 Americans, and about 100,000 people worldwide.

“Development of dysphagia [swallowing disorders] in these patients seems relatively inevitable, with a mean onset of three to four years,” says Michelle Troche, Associate Professor of Speech & Language Pathology. “The earlier the onset, the shorter their survival. We need to also understand whether these patients have cough disorders and whether it can be rehabilitated so that we can hopefully prevent aspiration pneumonia, which is a leading cause of death in PSP.”

Now, in a study funded by the CurePSP Foundation, Troche and Lisa Edmonds, Associate Professor of Communication Sciences & Disorders, are studying the complex communication, swallowing, and cough disorders which occur because of PSP and testing the feasibility of several treatments to rehabilitate these functions in PSP.

[Read the study by Troche, Edmonds and their co-authors, "Immediate Effects of Sensorimotor Training in Airway Protection (smTAP) on Cough Outcomes in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: A Feasibility Study."]

As part of this larger study, Troche and other researchers have identified that pervasive cough and swallowing deficits are, in fact, prevalent in PSP. Specifically, people with PSP have problems detecting that they should cough (when presented with a cough-inducing stimulus) and they also have trouble producing the cough — and this is worse than what is seen in patients with Parkinson’s disease. The study also identifies some therapies that hold potential for improving cough and swallowing function and improving patients’ quality of life.

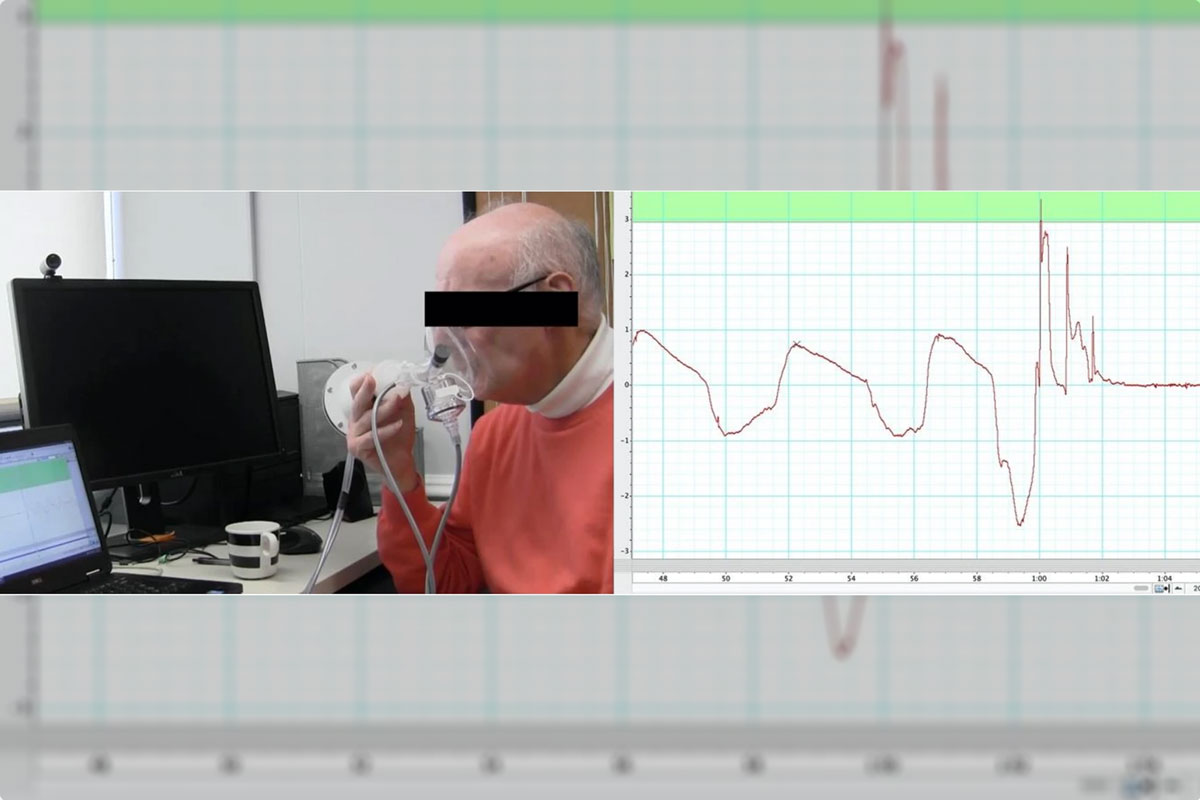

As part of their study, the team recently published a paper in the journal Dysphagia, where they described the use of a technique called sensorimotor training in airway protection (smTAP), co-developed by Troche, to see if they could “upregulate” cough function in 15 participants with PSP. During smTAP, the participants were given capsaicin, a mild irritant derived from chili peppers, to make them cough involuntarily. With verbal prompting, and by watching a live graph of their performance, 14 of 15 participants increased their cough strength across 25 repetitions, with 11 participants achieving improvements of more than 10 percent.

“This study is the first to demonstrate the ability of people with PSP to immediately upregulate cough function, providing preliminary support for the feasibility of cough rehabilitation in this population with this novel treatment approach,” the authors write.

Swallowing and language dysfunction can have a huge impact on quality of life. But we’re seeing that much can be done. The key is to make an early assessment so that patients can get the appropriate intervention they need.

— Michelle Troche, Associate Professor of Speech & Language Pathology

In other research that is still ongoing, Troche and other researchers are studying dysarthria, a speech disorder common in PSP patients that damages speech production. To date, they have found some evidence that a device called SpeechViveTM, which produces loud talking sounds in the ear of the wearer, automatically can stimulate louder speech in some people with PSP. They have also tested, with some success, a technique called Verb Network Strengthening Treatment (VNeST), developed by Edmonds, which emphasizes the use of a core group of verbs as a means of helping people improve retrieval of meaningful words and sentences.

Troche cautions that these studies are preliminary and that there is much work to be done to confirm and build on their findings. But she is clearly optimistic.

“Swallowing and language dysfunction can have a huge impact on quality of life,” she says. “But we’re seeing that much can be done. The key is to make an early assessment so that patients can get the appropriate intervention they need. And all we are learning really suggests that speech therapists play a very important role in improving health and quality of life in PSP.”