Fifty-two years ago, as president of his high school’s student council in Teaneck, New Jersey, Jay Heubert led fellow students in challenging a racially discriminatory tracking policy that placed most Black kids in large, low-track classes where students crowded around to watch their teacher dissecting a single beef heart. Honors students in small classes each got their own beef heart to examine.

Heubert’s interest in education and civil rights came from family members who had fled the Nazis. In elementary school, he helped his parents elect a school-board slate committed to voluntary desegregation of the local schools, the first school district in the nation to do so.

He only learned much later that his maternal aunt had played a vital role in securing repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act as the clerk to the Committee on Immigration of the U.S. House of Representatives. When repeal was enacted in 1943 with the Magnuson Act, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt gave her a pen he had used sign to the repeal into law, along with an authenticating letter. The pen and letter are now exhibited at Angel Island in California.

EARLY INSPIRATION Jay Heubert’s grandmother (center), mother, Lisa Heubert, nee Wydra (right) and aunt, Miriam Wydra, later Miriam Mendell, fled the Nazis. His mother helped desegregate the schools in Teaneck, New Jersey, and his aunt worked for the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

These events happened a long time ago, but the issues are still front and center today. Many students of color are still denied high-quality education: “Look at what’s going on now around race and in acts of hatred toward Blacks, Asian Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, and other groups,” says Heubert, who was recently named Professor Emeritus of Law & Education after announcing his retirement this spring. (Heubert also served from 1998 to 2019 as Adjunct Professor of Law at Columbia Law School.) “Sadly, such acts of discrimination are still taking place every day right now.”

Watch the retirement celebration in honor of Professor Jay P. Heubert

[Watch an online retirement party celebrating Jay Heubert, at which speakers included Gary Orfield; Distinguished Research Professor of Education, Law, Political Science and Urban Planning at the University of California, Los Angeles; TC alumnus John King, former U.S. Secretary of Education; TC alumna Carol Burris, Executive Director of the National Education Policy Center; Rhoda Schneider, General Counsel and Senior Associate Commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education; Dennis Parker, director of the National Center for Law and Economic Justice; and, from TC, Aaron Pallas, Arthur I. Gates Professor of Sociology & Education; Jeffrey Young, Professor of Practice in Education Leadership; Provost Stephanie Rowley; and Janice Robinson, Vice President for Diversity & Community Affairs.]

Focus on Discrimination

Heubert has drawn on those same wellsprings throughout a career that has focused on discrimination in education, including the national effort in recent decades to define what students should know and be able to do at different stages of their studies and to determine to what extent all students are actually acquiring the knowledge and skills they need.

Combining his expertise in law and education — which reflects stints as a high school teacher in rural Appalachia, an advisory specialist on school desegregation in Philadelphia, a trial attorney in the Education Section of the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, and Chief Counsel to the Pennsylvania Department of Education — Heubert has probed whether and how student testing for tracking, promotion, and graduation is advancing or inhibiting the learning and life chances of disadvantaged students. He completed some of this work as a Carnegie Scholar with support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Test scores by themselves don’t improve learning any more than a thermometer by itself cures a fever. Both give us information you can use if you are then willing to do what it takes to cure the patient. In many places, though, states and school districts are not willing or able to invest what it costs to make such improvements.

—Jay Heubert, Professor Emeritus of Law & Education

“The hope is that such tests will give us important information on which students need help, and what kinds of help they need. But testing can help students improve only if the results are used to improve the quality of education that low-achieving students get,” he says. “I’m not against testing. Quite the opposite — we desperately need to know which students — and which kinds of students — need more support, and good tests, properly used, can give us such information. But test scores by themselves don’t improve learning any more than a thermometer by itself cures a fever. Both give us information that we can use to address the problem. But as my colleague Michael Rebell [TC Professor of Law & Educational Practice] has shown, many states and school districts are not willing or able to invest what it costs to make such improvements. And if you set high standards but don’t do what it takes to help students meet those standards, then putting kids in low-track classes, or holding them back, or denying them high-school diplomas amounts to punishing children for not knowing what their schools have never taught them. That is simply unacceptable — educationally, legally, and ethically.”

Ironically, Heubert notes, standards-based reform can reinforce persistent, widespread segregation in housing and schools. “If wealthier parents buy homes in neighborhoods served by schools that have the highest test scores, that can exacerbate already-severe housing and school segregation,” he says. “Yet, as the eminent scholar and practitioner Carol Burris [Heubert’s former TC student] has shown, with careful preparation and support, schools can serve most students in high-level classes. Even many initial low-achievers can eventually meet high standards, in mathematics, for example, passing IB and Advanced Placement examinations. This helps to close the achievement gap significantly.”

After teaching in North Carolina in the early 1970s, Heubert worked for several years as an advisory specialist on school desegregation and gender equity in the School District of Philadelphia. The experience was in many ways a window onto the larger landscape of American education.

“The director of the district’s school desegregation office was a dynamic Black woman who had once helped lead one of the largest NAACP chapters in the U.S. She was a powerful mentor to me for four years,” he recalls. “And Title IX had just come in. But Frank Rizzo had become Mayor of Philadelphia during that time. He got elected by saying, basically, ‘Vote for me because I’m white,’ and he appointed members of the board of education. So we didn’t do much desegregating. I decided to go to law school so I could sue people like Frank Rizzo. And I completed a doctoral degree in education so I could work as an educator in communities pursuing progressive educational agendas.”

Frank Rizzo had become Mayor of Philadelphia during that time. He got elected by saying, basically, ‘Vote for me because I’m white,’ and he appointed members of the board of education. So, we didn’t do much desegregating. I decided to go to law school so I could sue people like Frank Rizzo. And I completed a doctoral degree in education so I could work as an educator in places pursuing progressive educational policies.

—Jay Heubert, Professor Emeritus of Law & Education

After earning his law and education degrees at Harvard, Heubert made good on those goals. As a trial attorney in the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, he helped assemble evidence showing that Mississippi had acted with intent to discriminate when, soon after James Meredith applied to be the first Black student at the University of Mississippi, the state adopted a minimum cutoff score on the American College Test (ACT) for freshman admission to all its historically white colleges.

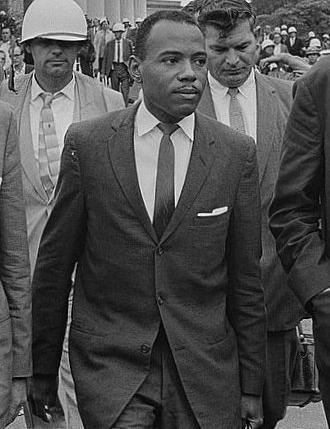

HISTORIC JUDGMENT While at the U.S. Department of Justice, Jay Heubert helped gather evidence that the state of Mississippi adopted a new discriminatory admissions policy when James Meredith (above) applied to be the first Black student at the University of Mississippi. In 1992, in the Fordice decision, the Supreme Court unanimously accepted the argument that the state’s admission requirements were unconstitutional. (Photo: Public Domain)

“We took the deposition of the registrar at Ole Miss,” Heubert recalls. “Now, ACT policies say you shouldn’t set a fixed cutoff score for admission, but Mississippi had not only created such a cutoff but picked a number that most Whites but very few Blacks could meet. When we asked the registrar, ‘How did you pick that cutoff score,’ he said, ‘Oh, we pulled that out of the air during the Meredith days. Don’t ask me about that or I’m apt to tell secrets.’”

In 1992, in United States v. Fordice, the U.S. Supreme Court accepted this argument. It ruled unanimously that Mississippi’s adoption and use of the ACT had been the product of an unconstitutional intent to discriminate against Blacks.

Educational Innovator

Heubert’s priorities since he became a full-time professor have proceeded on two parallel tracks – as a researcher and leading authority on high-stakes testing, the role of law in school reform, and the obligations of charter schools to serve students with disabilities; and as a teacher and educational innovator who has sought to promote interdisciplinary collaboration among lawyers, educators and policymakers.

In 1999, with eminent sociologist Robert M. Hauser, Heubert was co-editor of High Stakes: Testing for Tracking, Promotion, and Graduation, a Congressionally-mandated report by the National Research Council’s Committee on Appropriate Test Use, which Hauser chaired. Hauser and Heubert presented the report’s recommendations to the House and Senate education committees, and at the U.S. Department of Education.

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights subsequently relied heavily on High Stakes in its national resource guide on high-stakes testing, which was scheduled to be distributed to every school district in the country. But the guide was permanently embargoed soon after President George W. Bush took office.

The National Research Council also created a new standing committee, the Committee on Educational Excellence and Testing Equity, whose mission included building on the findings and recommendations of High Stakes. As a member of that committee, Heubert subsequently served as a coeditor for Understanding Dropouts: Statistics, Strategies, and High-Stakes Testing (2001), which focused on the relationship between high-stakes testing and the likelihood of students dropping out of school.

“The single strongest predictor of who will drop out is who is retained in grade, even once. Counter-intuitively, low-achieving students who are promoted anyway do much better academically, socially and in in terms of dropout than similar low achievers who have been held back .” Heubert says, “And who are the kids who most often get retained in grade and later drop out? It’s low-SES kids, Black kids, Latino kids, English-language learners, and students with disabilities.”

Right now, Heubert notes, a number of states are considering holding back students who performed poorly in online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic. “I fear the students retained will once again be mostly low-SES students, students of color, immigrant students, and students with disabilities,” he says. That would be a serious setback, and this debate is going on right now, today.”

Another major publication of Heubert’s is Law and School Reform: Six Strategies for Promoting Educational Equity (Yale University Press, winner of the 2000 American Educational Studies Association Critics’ Choice Award), which he edited and for which he wrote the opening chapter. The book — a study of major law-driven education reforms of the latter half of the 20th century, including school desegregation, school finance reform and enforceable performance mandates, was a key source for the nationally televised PBS series School: The Story of American Public Education for which Heubert was interviewed.

Heubert has also won teaching awards at Harvard and Teachers College. Graduating students at the Harvard Graduate School of Education twice chose him as their faculty commencement speaker and the school itself gave him its prestigious distinguished alumnus award.

Heubert also founded, and for the past 30 years has co-led with leading education-law attorney Rhoda Schneider, the School Law Institute, a national professional-education program for superintendents, principals, teachers, school attorneys and others.

The Institute was born of Heubert’s belief in the growing importance of bringing “multidisciplinary perspectives — those of law, policy analysis, education, and related disciplines — to bear on the task of improving teaching and learning, especially for students who have been denied equal educational opportunity.

The Institute’s topics have included implicit bias, serving immigrant students, school choice, school safety issues, serving students with disabilities, standards and accountability, and free speech, and in some years, some special extras — for example, in 2016, when then-U.S. Secretary of Education John King, Heubert’s former TC student, turned up to lead students through an analysis of the federal Every Student Succeeds Act.

RELEVANT FOCUS The issues Jay Heubert has studied, including racial discrimination, voting rights, school segregation and high-stakes testing, are very much in the limelight today. Above: A Black Lives Matter rally during spring 2020. (Photo: AP)

Changing with the Times

In recent years the law has changed more rapidly than usual as the Trump administration significantly altered civil-rights law and policy. In Fall 2019, Heubert took a semester-long sabbatical to assess such changes in civil-rights law, policy, and practice, and to update his syllabi accordingly. He’s explored the racial-equity implications of the COVID-19 pandemic, the impact of the Black Lives Matter movement in the aftermath of widespread police killings of Black Americans, and the import of recent decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court that affect civil rights – particularly voting rights, immigration policy and practice, rights based on free speech and religion, and the rights of those who identify as LGBTQ.

Most recently, under the Biden administration, a number of Trump civil-rights policies have been altered or reversed. There are new developments every day. So why retire now?

There is a great need for people who know how to make changes at the school and school district level. Integration of neighborhoods, schools and classrooms must remain a key priority to improve education for all.

—Jay Heubert, Professor Emeritus of Law & Education

“I’ve had many exciting and fulfilling experiences in the civil rights arena,” Heubert says, “and I’ve been able to bring those experiences into my teaching and research with support and inspiration from remarkable professional colleagues and the most committed and conscientious students imaginable. But after 45 years in the field, 35 as a professor of law and education, I’m ready to try something a little different. I still follow current developments, of course, and all the changes taking place, but it’s a bit more relaxed now that I don’t have to update my course readings on a daily basis. I look forward to more time with my dear friends and family, especially as the pandemic recedes, and to exploring other interests for which I haven’t had time while teaching. I will also stay in touch with my wonderful colleagues and former students, a great many of whom are making critical contributions in their own lives.

“One further thought: In the past, I thought my main responsibility was to explore with my students — patiently, responsibly, with empirical evidence — the many ways in which we as a nation are still fighting the Civil War. Until fairly recently, many of my students seemed to think that the important discrimination problems had been solved decades ago, and that all we needed to do now was to tie up loose ends. Now, though, my students have grown increasingly aware of how much discrimination there is, and of how much harm it does, both to the oppressed and the oppressors. They understand that integration of districts, schools, and classrooms remains a key priority to improve education for all, and they are committed to making those changes happen.”

Heubert identifies a further key ingredient for social progress: Being able to talk about our disagreements.

“Given the extreme political polarization in our society, it’s become virtually impossible for people on different sides even to discuss their differences, much less to find common ground,” he says. “I don’t have answers to that question, but if such communication is possible anywhere, it should be possible in college and university classrooms. That’s what teaching is about, and it’s really why I wanted to work in academia. And I’ve never regretted that decision.”