Christopher Emdin appreciates the unruly. He likes to quote Septima Clark, the undersung educator and activist who propounded mass public education during the civil rights movement, and who once said: “I have a great belief in the fact that whenever there is chaos, it creates wonderful thinking. I consider chaos a gift.”

Emdin — Associate Professor of Science Education in TC’s Department of Mathematics, Science and Technology, Associate Director of the Institute for Minority and Urban Education, and noted public intellectual beyond the college walls — has emphasized throughout his career the inchoate knowledge and embedded genius that manifest in the classrooms that educators too often put down as loud, unstructured, out of control.

[Read Emdin’s recent interview with Larry Ferlazzo in Education Week.]

To tap into this genius, Emdin has proposed “reality pedagogy” — in which educators learn the complex realities in students’ lives, infuse the curriculum with this understanding, and cultivate relationships with students in this spirit. His 2016 best-seller For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood… and the Rest of Y’all Too: Reality Pedagogy and Urban Education, a New York Times best-seller, was part manifesto, part how-to guide, complete with “Seven C’s” for teachers to implement.

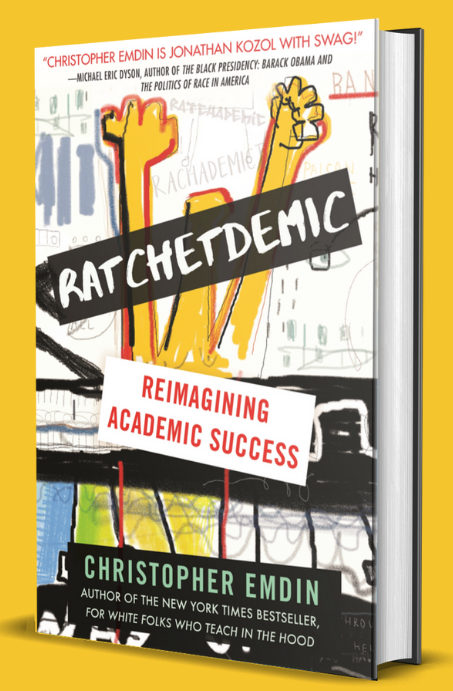

Now, Emdin is going one level deeper, with a new volume that contains no handy steps to follow. Instead, in Ratchetdemic: Reimagining Academic Success, out this week from Beacon Press, Emdin exhorts educators, if they are to truly serve their students, to liberate themselves.

ACING THE GRADE-BOOK “Ratchetdemic is a timely and essential resource for teachers, parents, and whoever else needs this compelling and accessible and above all absolutely refreshing take on pedagogy,” said author Jacqueline Woodson in pre-publication review. “Here’s to more and more classrooms being filled with learning, healing, and joy.” (Photo courtesy of Beacon Press)

Emdin was one of those turbulent kids himself, as a teenager in Brooklyn and the Bronx, finding more fulfillment in crafting rap lyrics than in the pedagogy most of his teachers proposed. Later he worked the other side of the desk, a freshly credentialed teacher attempting to impose order and authority, and failing, until he began to sense a different way.

Over the years, as a scholar and consultant, Emdin has engaged with countless educators and administrators who, though often animated by the best intentions and equipped with diversity, inclusion, and anti-racism concepts, still seemed to lose their way. Some burn out, some grow cynical, some slowly conform to norms enforced top-down in an education system that in fundamental respects, Emdin argues, never truly changed.

Ratchetdemic challenges educators to examine whether what they are delivering is actually education — in its fullest sense — at all. The “true mark of being educated,” Emdin writes in the introductory chapter, is to “achieve a state of consciousness that allows one to operate in the world having mind, body, and spirit activated, validated, and whole without distortion or concession as one acquires all essential knowledge — academic knowledge, knowledge of self, knowledge of how to navigate one’s immediate surroundings, knowledge of the systems in which one is embedded (particularly those that are structured to disempower), and knowledge of the world.”

Education in this spirit is a mutual task, self-reflexive if it is to succeed: “Both getting to that point and helping youth get to that point are the responsibilities of the educator,” he writes. “The ratchetdemic educator recognizes that they must pursue and model their own work toward freedom from the constraints of institutional structures. Students must see you struggle with the tension between what is expected of you and what is the right thing to do.”

“To find your ratchet is a struggle,” Emdin says, reached by phone recently. “But to me it’s the beautiful struggle.” In the tradition of hip-hop MCs, he has crystallized his theory with a piece of wordplay that carries layered meanings. To act ratchet, a widespread current slang term, is to be messy, uninhibited, possibly vulgar, definitely authentic. (Those kids causing a scene in the classroom? Probably acting ratchet.) But ratchet, Emdin points out, is a useful, accessible tool; and in the New York parlance of his upbringing, it serves as a weapon. “Ratchet has always been the secret weapon,” Emdin says. “It’s the not-established, secret weapon to unlock new possibilities. It’s the raw honest culture of the marginalized.”

Ratchetdemic is a conscious entry in a lineage of critical pedagogy that Emdin traces to Paulo Freire, Gloria Ladson-Billings, and even W. E. B. Du Bois, who was once, Emdin notes, a teacher-training graduate in Tennessee whose first rural schoolhouse job brought home how the system will extinguish young people’s organic enthusiasm in service of reinforcing the social order. “Du Bois went through this too, and so will you,” Emdin says, of educators reaching similar realizations today. “The difference is that back then, there was no language to express the need for that veracity and rawness. We’ve never taken up that ratchetdemic revolutionary spirit in the way that it should. And this may be our season to do so.”

THOUGHT LEADERS In conversation with Dr. Benjamin Chavis, former head of the NAACP, Christopher Emdin discussed core concepts from Rachetdemic and what educators need to know.

As Emdin tells it, while the ideas have long percolated in his work, the events of the past year and a half accelerated the urgency. “We’ve gone through a pandemic, we’re reckoning with this whole issue around the valuing of Black lives, young people have been in virtual school for a year and change, and we have this small moment to really reimagine.” Today’s increased focus in many fields on diversity and inclusion follows years of liberal or progressive initiatives in education whose record, Emdin argues, has been deeply inadequate to the challenge.

Meanwhile, it is young people — Black, brown, queer, Indigenous, marginalized — who have formed the new social and protest movements that are challenging the power structure and modeling new ways of living. That’s ratchet in action, Emdin says: “Young people are in a season of rawness, they’re unapologetic and they’re honest and they’re pushing against these established norms in powerful ways that schools don’t yet have a language to understand. They’re so far ahead of us — and this book is a call to catch up.”

Running through Ratchetdemic is a kind of consciousness journey that draws abundantly on Emdin’s own story, from city kid nearly lost to the school system to professor in a prestigious, liberal — but by no means flawless — education faculty, and on numerous examples from his encounters and research. The focus is on stories of Black educators, who have typically had to suppress their own ratchet in their career formation and risk visiting the same cognitive violence on their students — or burning out fighting it. Emdin admits to this emphasis, but as with For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood..., he believes this new book will be useful to all interested readers. “Ratchetdemic is for Black and brown educators who have lost their way… and the rest of y’all too,” he says. “Both books are for everyone, but I kind of wanted to center the experience and needs of Black and brown educators, and I feel other folks can glean from it too.”

Radical? Revolutionary? Emdin welcomes the descriptors. “We have all been complicit in not letting folks be truly free,” he says. “I want people to read this book and say, ‘Wow, I have been complicit in robbing a certain population of their genius. I have been part of a system that has not recognized that genius comes in various forms. And I want to be different.’” In enforcing its confining expectations of Black and brown youth, the system has not only made accomplices of educators of all backgrounds, Emdin says, but has robbed them of some of their own freedom. Educators who do the work of liberating themselves will find one another, he believes — and just might spark a fundamental transformation. “This book is an invitation to collective freedom, in pursuit of a transgressive pedagogy.”

— Siddhartha Mitter