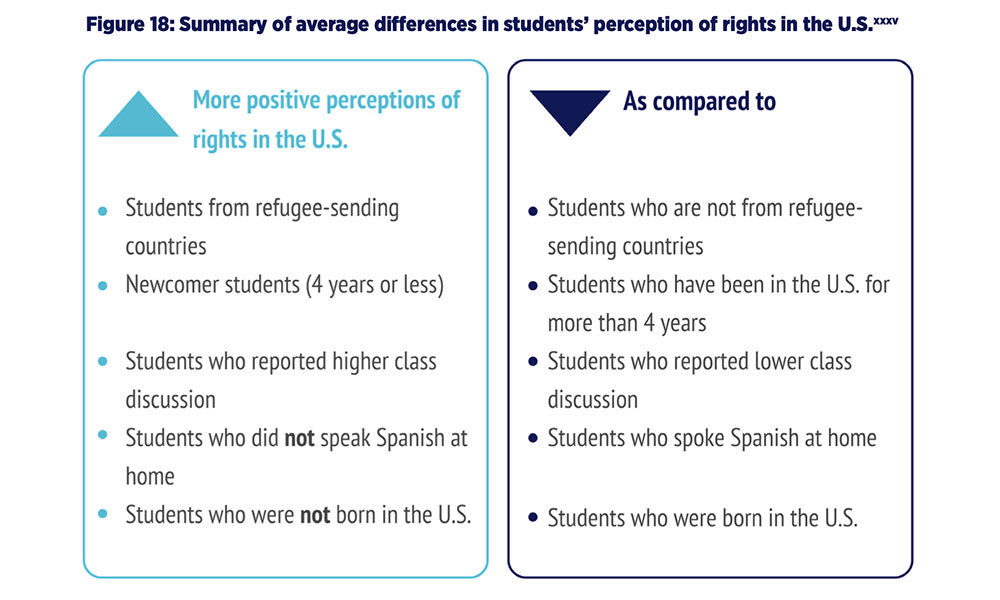

Newcomer immigrant and refugee students have a stronger sense of belonging at school and higher expectations that their rights will be protected than students who have been in the United States for longer (more than four years), or who were born here — including second-generation immigrants. And while students in both groups are interested in political and social issues, they tend not to view themselves as civic actors.

These are findings of a study led by S. Garnett Russell, Associate Professor of International & Comparative Education at Teachers College, published in a new report, Fostering Belonging and Civic Identity: Perspectives from Newcomer and Refugee Students in Arizona and New York.

INCLUDING MANY VOICES S. Garnett Russell and her team surveyed 286 students representing 49 different countries of origin who spoke 39 different languages. (Photo: TC Archives)

The findings of the study, funded by the Spencer Foundation, may be “a result of newcomers’ high aspirations and expectations or due to the fact that students who had been in the U.S. longer were more aware of the disadvantages they would face and had more exposure to systemic discrimination and exclusion of their communities outside of school,” Russell writes with her co-authors, TC doctoral fellows Amlata Persaud (Ed.D. expected 2021, International Education Development); Paula Mantilla-Blanco (Ph.D. expected 2023, Comparative & International Education); Katrina Webster (Ph.D. expected 2025, Comparative & International Education); and Maya Elliott (M.A. ‘20, Comparative & International Education). [Click here to read stories on Persaud, Mantilla-Blanco, Webster and Elliot.]

The study highlights the important role that schools play in fostering a sense of belonging in increasingly multicultural student populations. It also shows that schools can do much to either encourage or inhibit civic values and civic engagement in all students.

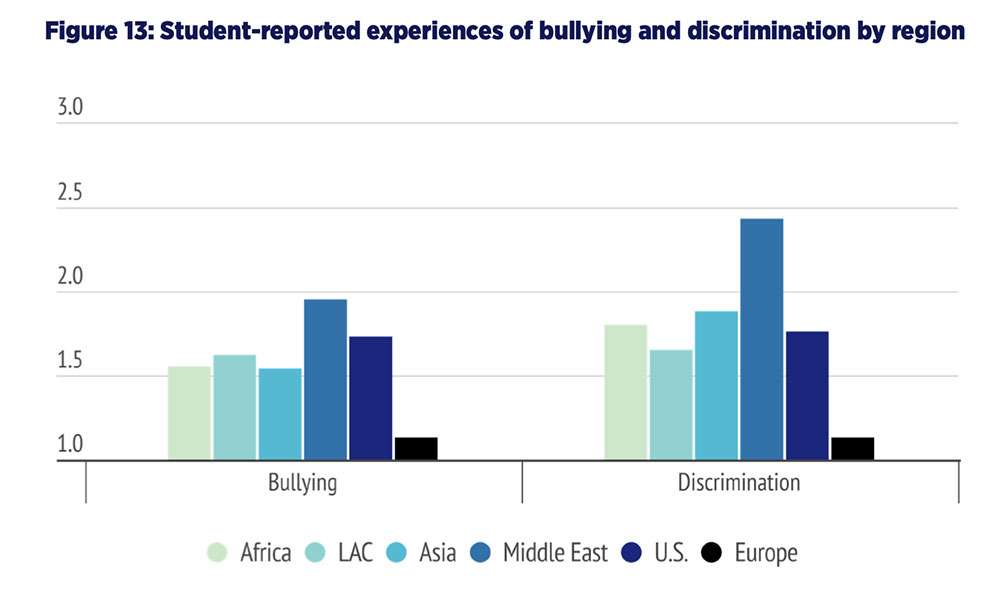

HOSTILE ENVIRONMENTS Being bullied is a fact of life for many students from immigrant families, but to which degree varies by what ethnic and cultural groups they belong to.

Previous research showed the importance of school climate and school relationships in facilitating a sense of school belonging in students, while other studies have drawn the connection between school belonging and civic identity. In the TC study, students tell in their own voices how well their schools are preparing them to take an active role in American democratic processes. The study is based on surveys, interviews and classroom observations, conducted during the 2018-2019 school year, of students at two high schools in Arizona and two in New York with high numbers of newcomer immigrant and refugee students.

The United States has the highest number of immigrants in the world. About 14 percent of the population was born in another country, and 25 percent are first- or second-generation immigrants. A 1982 U.S. Supreme Court ruling (Plyer v. Doe) upheld the right of all children — immigrant or U.S.-born — to an education. Schools are required to educate all children without inquiring about their immigration status.

REALITY CHECK Students — especially those who are refugees — may arrive with high expectations for the rights they will enjoy. Their perceptions change with time.

Russell and her research team surveyed 286 students representing 49 different countries of origin who spoke 39 different languages.

Additional interviewees included 19 teachers, 14 school administrators, and four staff members from school districts and refugee resettlement organizations. Among the researchers’ additional findings:

- Students are interested in social and political issues such as immigration and gun control, but do not “connect those interests to civic engagement and generally [feel] disengaged and disempowered to bring about change.”

- Teachers often avoid discussing sensitive topics related to politics or identity in the classroom. But this can compromise the ability of students to develop civic capacities.

- School districts recognize the diversity of their students and provide services to newcomers and refugees, but they struggle to address individual students’ needs, including mental health challenges resulting from political violence, or economic or environmental disasters in the countries they had fled. Schools are challenged with “recognizing and celebrating student diversity while at the same time fostering a sense of inclusion.”

- Newcomer and refugee students’ goals and aspirations for higher education and future careers are inhibited by teachers’ and school administrators’ diminished expectations for their success, as well as the schools’ inability to prepare students to meet their goals.

- While they feel a sense of belonging at school, immigrants often face discrimination outside of school, with students from Middle Eastern countries facing the most discrimination.

- Immigrant students’ views of citizenship are narrowly focused on their legal status and attaining legal citizenship instead of “participatory and engaged understanding” of citizenship “involving social change and empowerment.”

- Participation in civics-related clubs and class discussion was linked to present and future civic engagement of students, and participation in extracurricular activities and clubs correlated with a higher sense of school belonging.

The researchers make a series of recommendations, including:

- Increasing opportunities for students to initiate and participate in clubs and activities inside and outside of school;

- Improving newcomer and refugee students’ college and life readiness skills;

- Improving professional development for teachers to help them engage and support immigrant and refugee students;

- Encouraging greater family and community engagement in schools that serve newcomers.

The extent to which these students see themselves as civic actors will impact the country’s political and economic future. It is a matter of great priority that we more deeply consider how students’ sense of inclusion, belonging, and civic identity, fostered during their formative years at schools and in their communities, have important implications for them as individuals and as members of society.

The admission of immigrants and refugees declined sharply during the Trump Administration, but it is expected to resume climbing if President Biden succeeds in reversing Trump’s anti-immigrant policies. If that happens, new immigrants could arrive in the United States amid heightened “nationalistic discourse and a rise in anti-immigrant and anti-refugee sentiments,” the report says, adding that “the polarized political climate has spread to schools, which have experienced increased incidents of discrimination and xenophobia.” These trends have compromised the sense of inclusion and belonging at school and in communities that is essential for immigrant students to develop a civic identity.

In addition, the global COVID-19 health pandemic, by requiring students to learn remotely, has threatened the social connections that newcomer immigrants need to build and sustain “a sense of identity, civic engagement, and school belonging among all students,” the authors write.

“The extent to which these students see themselves as civic actors will impact the country’s political and economic future. It is a matter of great priority that we more deeply consider how students’ sense of inclusion, belonging, and civic identity, fostered during their formative years at schools and in their communities, have important implications for them as individuals and as members of society.”

— Patricia Lamiell

Vital Contributors: The student team that co-authored Fostering Belonging and Civic Identity

Students come to Teachers College to learn how to change the world — and, as research partners to faculty, they typically come with a broad range of experience that helps them get a jump on the process while they’re here.

KEY CONTRIBUTORS Top row, from left: Doctoral students Katrina Webster and Paula Mantilla-Blanco; bottom row, from left: Doctoral student Amlata Persaud and recent graduate Maya Elliot worked on the study led by S. Garnett Russell. (Photos: TC Archives)

The new study on immigrant students’ sense of belonging, just released by S. Garnett Russell, Associate Professor of Comparative & International Education, is a case in point.

While Russell, author of Becoming Rwandan: Education, Reconciliation, and the Making of a Post-Genocide Citizen (Rutgers University Press 2019), is a widely recognized authority on education in other cultures, three doctoral and one recent graduate played a critical role in the new effort.

They are:

Katrina Webster, a doctoral student (Ph.D. expected 2025) in the International & Comparative Education program and a Doctoral Research Fellow for the Office of International Affairs. Before joining the TC community, Webster developed academic enrichment programs for youth in Rwanda and has worked with the private sector, nonprofits, and multi-stakeholder partnerships to improve educational outcomes for the marginalized. As the daughter of a Guyanese immigrant, she believes that centering the voices and perspectives of newcomer immigrant and refugee students is crucial to the process of improving their experiences in U.S. public schools. “One surprising finding,” she writes, “that many of these students didn't connect their concerns about political and social issues to civic engagement, sheds light on the need to ensure all students feel empowered to effect change in their communities.”

Paula Mantilla-Blanco (Ph.D. expected 2023), a doctoral fellow in the Comparative and International Education program whose research interests include education in conflict and post-conflict contexts, narratives of violence and peace, and the connections between collective memories and identity. Most of her work focuses on Colombia, her home country, and on how youth perceive their own role in bringing about change. Working on this project about newcomer and refugee students in the U.S. has contributed greatly to Mantilla-Blanco’s training as a mixed methods researcher. More importantly, it has unveiled the many contradictions and tensions that high school students navigate, from the way external ideas about who “gets to belong” collide with students’ personal sense of belonging, to the tension between the issues students care about and what they think their role is in sustaining or challenging social realities.

Amlata Persaud, a doctoral student (Ed.D. expected 2021) in the International Education Development program. Persaud’s research focuses on the ways in which educators can work across boundaries and sectoral “silos” to promote international development. Additional research interests include education policy and planning, education financing, as well as monitoring and evaluation. Persaud says that while her work “entails macro-level policy analysis,” this project enabled her to “observe and connect with students and teachers in the classroom environment and to bring these perspectives into a policy analysis framework.”

Maya Elliott (M.A. 2020), a graduate of the Comparative & International Education program. Her research interests include inclusion of refugee, migrant and asylum-seeking students in host country schools’ systems and early childhood development. Her previous experience includes working with newcomer high school students, and thus she loved the focus of this research and the emphasis on hearing students’ own opinions and reflections when it comes to defining belonging and illustrating the changing ways in which young people are becoming politically active.