Michael Isaacs always knew he’d work in emergency medicine. He just couldn’t have guessed how — or that the emergency would grip the entire world.

The COVID pandemic has left him with an even deeper appreciation for his field, but also with a skepticism shared by many frontline workers and strong views about how policymakers should rethink their approach to infectious disease.

The son of a paramedic, Isaacs became an emergency medical technician while still in his teens. “I grew up around the organized chaos and battlefield treatment mentality. I loved being able to save someone dying on the street.”

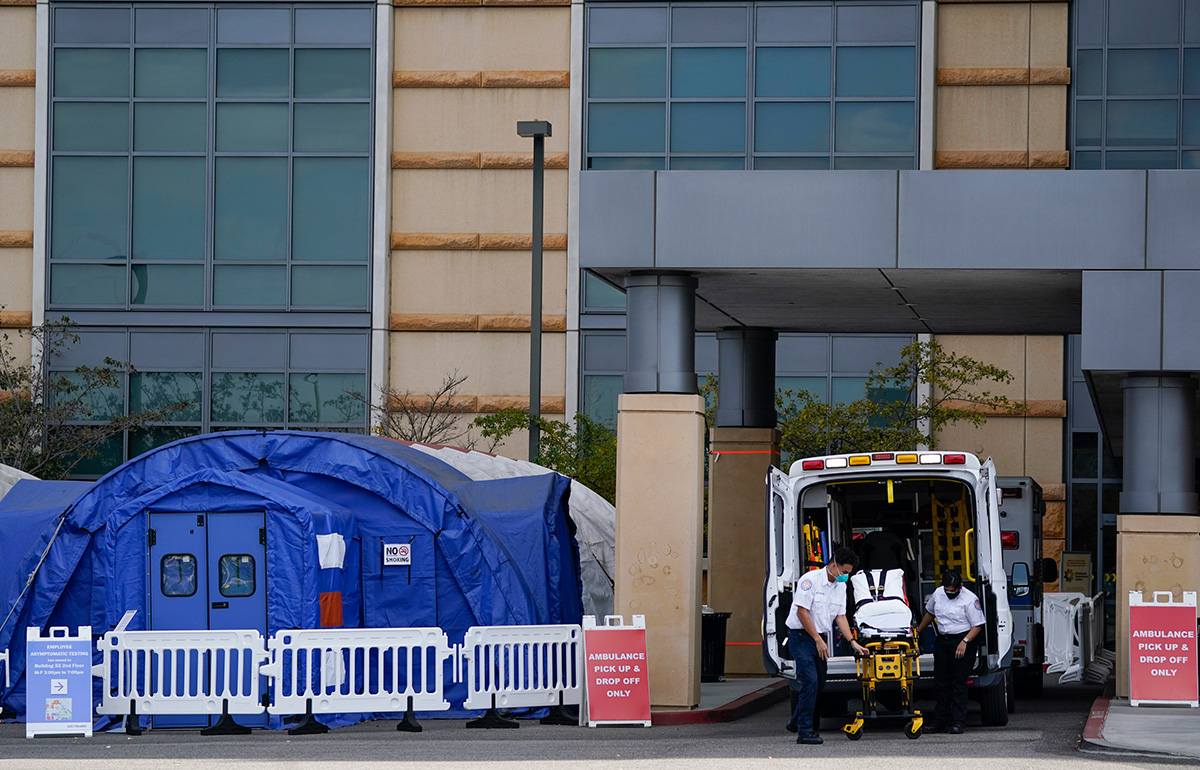

BEYOND CAPACITY Hospitals in California are so overcrowded with COVID patients that many are setting up tents outside for those who are less ill. (Photo: AP)

Flash forward to 2020. Isaacs — now 44, and a student in Teachers College’s online doctoral program in Nursing Education — was working as an emergency room travel nurse in California’s San Bernardino County, where, after a relatively quiet summer, COVID was resurging at a terrifying rate.

“Yesterday, we were at 112 percent capacity, with ICU patients in the ER,” he said, reached by phone one afternoon in late November. “You’ve got to segregate COVID patients or it will spread, and we’re doing that on the fly.” One ER he’s worked in has used zippered curtains to convert a fast-track space [for patients with minor ailments] into a hazmat area, where staff now wears Tyvek suits, N95 masks and goggles. Another has set up tents with portable heaters for COVID patients with milder symptoms. [On January 14th, according to the Los Angeles Times, officials had reported 24,973 new cases over the past seven days, which amounts to 1,169 per 100,000 residents. Visit the newspaper’s tracking site for current figures.]

Yesterday, we were at 112 percent capacity, with ICU patients in the ER. You’ve got to segregate COVID patients or it will spread, and we’re doing that on the fly.

—Michael Isaacs, Nursing Education doctoral student

On one level, Isaacs believes the country has made rapid progress in dealing with the pandemic.

“Back in March, New York City didn’t know what was coming, and no one knew how to treat the virus then,” he says. “Now, through trial and error, we know the progression, which patients are most vulnerable, and how to isolate them, and what drugs to give them. There’s a lot less death now.”

On the other hand, his assessment of federal and state responses echoes post-mortems of France’s Maginot Line and America’s fleet in Pearl Harbor.

“There’s no scientific logic in the decisions the government is making.,” says Isaacs, who self-quarantined after testing positive for COVID earlier in the fall. (He remained symptom-free.) “This is an all-or-nothing situation — you either shut it all down or don’t — so this business of closing the bars and gyms but not Walmart and McDonald’s isn’t stopping anything. It feels as though they’re doing things just to show they’re taking action.”

For Isaacs, TC’s nursing education program, with its focus on evidence, is the perfect antidote to such thinking. He’s taken an epidemiology class, engaged in discussions about COVID contact tracing, read literature reviews and conducted statistical analyses. “When officials issue new edicts now, my first thought is, show me the data,” he says.

This is an all-or-nothing situation — you either shut it all down or don’t — so this business of closing the bars and gyms but not Walmart and McDonald’s isn’t stopping anything.

——Michael Isaacs, Nursing Education doctoral student

Isaacs is also particularly focused on using technology to better prepare nurses and other workers for the unexpected.

“We’ve created these virtual worlds for other students, so why can’t programmers create nursing and medical situations that are true to life? It’s how this generation wants to learn, and it’s obviously ideal for the situation we’re dealing with right now.”

Meanwhile, he’s become only more committed to his work. “I’ve always felt that the ER is the foundation of healthcare. We stabilize patients and then hand them off to the specialists and rehab units. If the ER doesn’t do its job well at the start, the rest doesn’t happen. And we couldn’t have handled COVID without it.”